Introduction

On January 19, 1981, representatives of the United States and Iran assembled in Algiers at the invitation and good offices of the Algerian government to sign what became known as the Algiers Accords.1The Algiers Accords was a set of agreements that included the Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Concerning the Settlement of Claims by the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Jan. 19, 1981, 75 Am. J. Int’l L. 422 (1981) [hereinafter Claims Settlement Declaration]. Iran previously signed a similar agreement with Iran. See Bernard Gwertzman, U.S. and Iran sign accord on hostages: 52 Americans could be set free today, New York Times (Jan. 19, 1981).1 Most of the Accords’ provisions dealt with diplomatic relations and the main focus then provided that the U.S. would unfreeze Iranian assets held in the U.S. in exchange for the release of 52 American hostages in Iran.

One set of provisions would however go on to acquire greater importance.2See generally Charles N. Brower & Jason D. Brueschke, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal (1998). For a good summary of the events leading to the Algiers Accord and the beginning of the Tribunal, see generally Gunnar Lagergren, The Formative Years of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, 66 Nordic J. Int’l L. 23 (1997).2 Given the number of ongoing proceedings before U.S. and Iranian courts, the Algiers Accords provided for an Iran-United States Claims Tribunal that would hear the “claims of nationals of the United States against Iran and claims of nationals of Iran against the United States,”3Claims Settlement Declaration, supra note 1, art. II(1).3 as well as certain disputes between the two governments.4These were named “B disputes.” A third set of disputes, “A disputes,” concerned the interpretation of the Algiers Accords.4

Thirty-seven years running, the Tribunal’s output of more than 800 reasoned decisions, the bulk of which were rendered at a time when arbitral awards were relatively unavailable, is a remarkable resource for arbitration scholars and practitioners.5Richard Lillich, in one of the earliest yet major works on the subject, called this jurisprudence “a goldmine of information for perceptive lawyers.” Richard Lillich, Preface, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal 1981-1983 i, vii (Richard B. Lillich ed., 1984). But doubts about the relevance of the tribunal’s jurisprudence have arisen. See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 650; infra part V.5 This corpus has contributed to arbitration practice6See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 653 (“The mushrooming literature on the Tribunal’s decisions is further testimony that the Tribunal’s awards are sufficiently substantive for many commentators on international law.”).6 and in particular to the development of the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).7See, generally, Stewart A. Baker & Mark D. Davis, The UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules in Practice: The Experience of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal 1 (1992); see also Karl-Heinz Böckstiegel, Applying the UNCITRAL Rules: The Experience of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, 4 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 266, 266-67 (1986). An earlier version of the UNCITRAL arbitration rules applied to the Tribunal proceedings.7 The Tribunal’s jurisprudence has been cited by international courts and tribunals on substantive and procedural issues,8See, e.g., UP & C.D Holding Internationale v. Hungary, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/35, Award, ¶ 315 (Oct. 9, 2018) (citing Too v. Greater Modesto Ins. Assocs. & United States, Award No. 460-880-2 (Dec. 29, 1989), 23 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 378 (1991)). 8 and scholars analyze its jurisprudence as a source of international judicial practice.9See, e.g., Timothy G. Nelson, The Defector, the Missing Map and the “Hidden Majority” – Coping with Fragmented Tribunals in International Disputes, Transnat’l Disp. Mgmt. (2018).9

This role and importance has fallen from view as the number of scholarly works on the Tribunal has dropped in recent years.10But see Karen J. Alter, The New Terrain of International Law: Courts, Politics, Rights 183 (2014).10 Furthermore, the Tribunal has entered a “long twilight” phase where few, gargantuan and seemingly intractable disputes remain pending. Still, the Tribunal’s history and practice remain relevant and warrant our interest as a remarkable and under-investigated dataset. Retracing that history and practice with data analysis methods, this paper revisits past questions on the Tribunal and its work to inform today’s international arbitration practice and scholarship.

Part II below introduces the dataset and reviews in particular the overall outcome of the disputes before the Tribunal. Part III studies the Tribunal’s most important personnel: the judges, their terms on the bench, their coalitions, and the decisions they supported or opposed. This part also probes the Tribunal’s decision to share its work between chambers and the many advocates who appeared before the Tribunal. These two parts indicate that the Tribunal has been mostly successful at dealing with hundreds of cases without breaking down or be abandoned by one of the parties.

Part IV looks further into the Tribunal’s decisions and outcomes by studying the judges’ concurring and dissenting opinions and it discusses their role in shaping the Tribunal’s jurisprudence. Part V covers the topics treated in Tribunal awards and in the separate opinions. Part VI draws on the preceding material to explore whether the Tribunal’s experience should be discounted for its alleged political outlook—a common reproach that will likely accompany discussions of the Tribunal’s legacy and a reflection that is relevant to any dispute resolution system with party-appointed judges.

The Claims

The dataset

Under the Algiers Accords, all claims needed to be lodged with the Tribunal before January 19, 1982, or be deemed time-barred.1Awards on agreed terms did not enter the analyses below—although some of these awards have elicited interesting separate and dissenting opinions.1 The claims that were registered were then sorted between small claims valued at less than $250,000 where the U.S. and Iranian governments would represent their respective nationals; claims exceeding $250,000 where the individual claimants could stand on their own; and State-to-State claims.

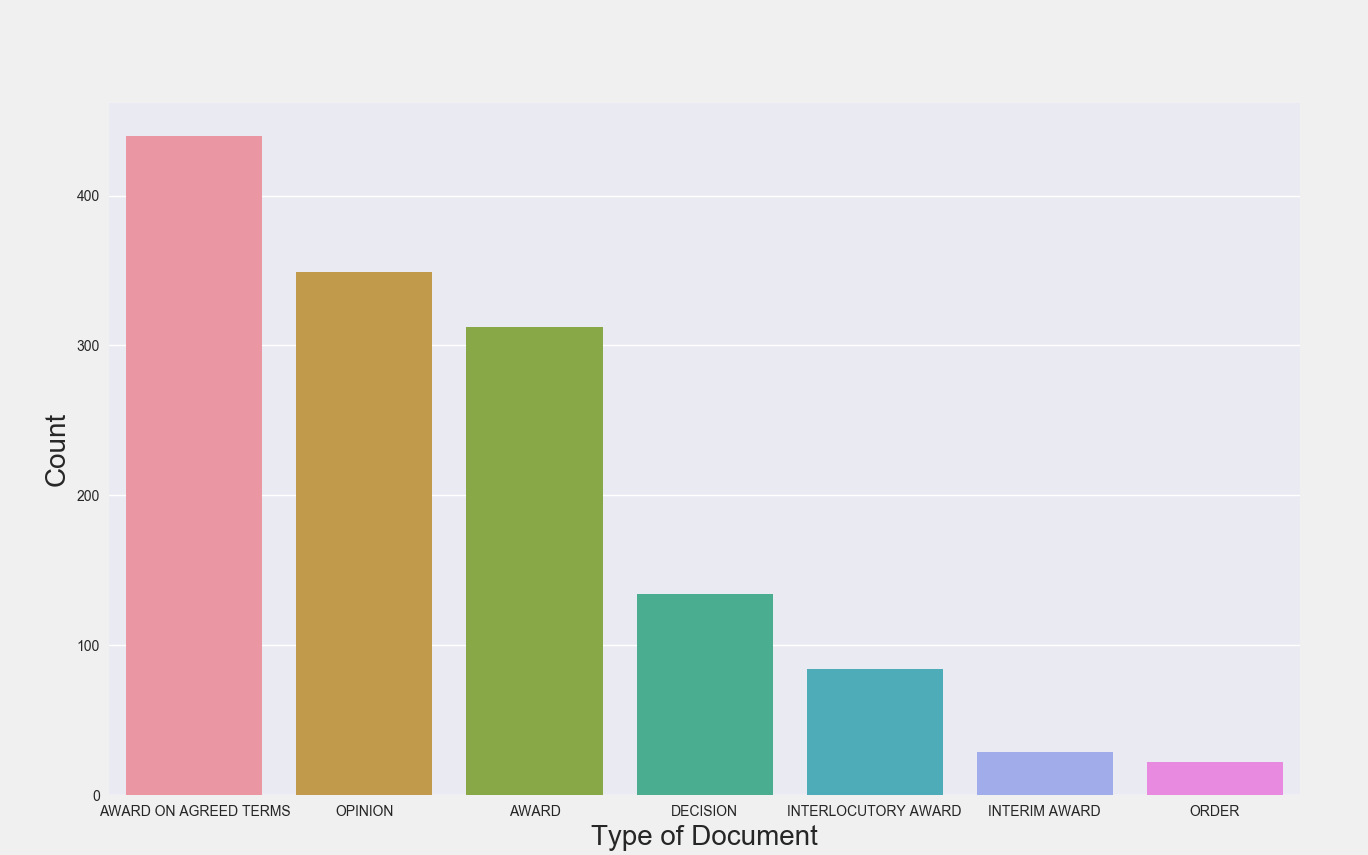

More than 3,800 claims were filed before that cut-off date.2David D. Caron & John R. Crook, The Tribunal at Work, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 133, 136 (David D. Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) [hereinafter Caron & Crook, The Tribunal at Work] (stating that there were 3,948 claims total); Maciej Zenkiewicz, Judge Skubiszewski at the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, 18 Int’l Cmty. L. Rev. 151, 154 (2016) (stating that 3,860 claims were filed, but they acknowledge the discrepancies between different authors on the exact figure); Lagergren, supra note 2, at 27 (stating that 3,836 claims were filed: “2,782 claims of less than U.S. $250,000, so-called ‘small claims’, 964 larger claims and 70 state-to-state claims”). The Tribunal’s website remains vague about the exact number, only mentioning that “[a]pproximately 1,000 claims were filed for amounts of $250,000 or more, and approximately 2,800 claims for amounts of less than $250,000.” About the Tribunal, Iran-United States Cl. Trib., https://www.iusct.net/Pages/Public/A-About.aspx.2 Most claims did not result in an award, however, as many were settled. One of the Tribunal’s great successes was to encourage the parties to settle their disputes3Awards on agreed terms did not enter the analyses below—although some of these awards have elicited interesting separate and dissenting opinions.3 and to provide a “relatively apolitical setting substantially walled off from other areas of bilateral conflict” between the two governments.4Caron & Crook, The Tribunal at Work, supra note 13, at 140; but cf. id., at 145 (criticizing the Tribunal’s willingness to push for settlements). The Iranian and U.S. governments notably agreed to a lump-sum payment that settled most small claims and some B claims between them. United States v. Iran, Award No. 483-CLTDs/86/B38/B76/B77-FT (June 22, 1990), 25 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 328, 330.4 This development is readily observable from Figure 1 below, which records the full dataset of published decisions broken down by type of document. A sizeable 33% of the Tribunal’s output consisted of awards on agreed terms, which sanctioned the settlement of the parties.5According to Brower and Brueschke, nearly half of the awards issued by the Tribunal were on agreed terms. Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 14.5

Of the cases that were not settled or abandoned, the judges have dealt (so far) with several hundreds of them, with just a few claims, all of them between the US and Iran directly, still pending as of late 2018. This impressive output goes a long way to explaining the importance of the Tribunal’s practice for international dispute settlement. Although some judges and parties originally expected the Tribunal to last for no more than three years,6See George H. Aldrich, The Selection of Arbitrators, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 65, 68 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000).6 the importance of the Tribunal’s work came to exceed its contemporary equivalents,7Over the same course of 12 years when the Tribunal rendered 90% of its awards (i.e., 1981 to 1993), the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a dozen judgments and orders on provisional measures, and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) oversaw less than 10 arbitrations. See Michael Waibel & Yanhui Wu, Are Arbitrators Political? Evidence from International Investment Arbitration (2017), http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~yanhuiwu/arbitrator.pdf. Cf. Brice M. Clagett, The perspective of the claimant community, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 59, 62 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (“All in all, disposition of virtually all of the large private claims . . . within twelve years is not a disgraceful record.”).7 especially at a time when arbitration, albeit on a rise, had not reached the prevalence it has today.

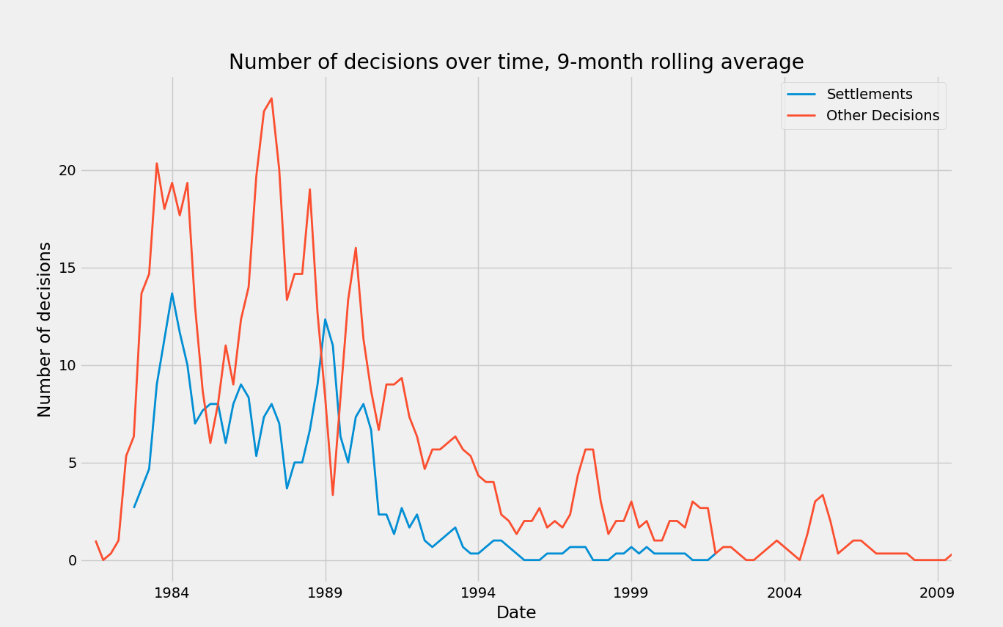

Most of this output came in the Tribunal’s first decade. After slow beginnings, the Tribunal reached an impressive pace until 1991-19928Caron & Crook, The Tribunal at Work, supra note 13, at 133 (describing the period between mid-1982 to 1991 as “the Tribunal’s most productive period”).8 when it started its long twilight. Since then the Tribunal has been facing cases directly between the U.S. and Iran, often based on sensitive contracts (e.g., weapons) and more politically fraught disputes. Figure 2 retraces the distribution of awards and decisions published over time, distinguishing between awards on agreed terms and other decisions.

Remarkably, Figure 2 marked a slump in 1984, which represents the aftermath of the “Mangard incident” where two judges appointed by Iran assaulted third-party judge Nils Mangard on the steps of the Tribunal on September 3, 1984. This incident “pretty well shut [the Tribunal] down for several months until the two Iranian judges on the Tribunal who were involved in the incident were removed from the scene and replaced by gentler sorts.”9See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 657.9

Outcomes

Another interesting feature of the Tribunal’s organization was that Iran’s liabilities as decided by the Tribunal or under settlement agreements were supposed to be paid out of a $1 billion fund initially seeded with Iranian assets in the U.S. That fund, however, had to be replenished as soon as its assets fell under $500 million, and Iran’s failure to do so starting in the 1990s led to several disputes aimed at interpreting Iran’s obligations in this respect.10Sean D. Murphy, Securing Payment of the Award, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 299, 301-02 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000).10

The sums awarded ran from $10011Baygell v. Iran, Award No. 231-10212-2 (May 2, 1986), 11 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 72, 75 (reimbursing the claimant an outstanding debt for an unused plane ticket).11 to $68.2 million12Sedco Inc. v. Nat’l Iranian Oil Co., Award No. 309-129-3 (July 2, 1987), 15 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 23, 185.12 without interest, which was often set at 10% or 12%. The amounts awarded to U.S. claimants in contentious proceedings, however, are dwarfed by those resulting from settlement: $495 million out of a total of $2.14 billion as of 1998.13Koorosh H. Ameli, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, in The Permanent Court of Arbitration: international arbitration and dispute resolution: summaries of awards, settlement agreements and reports (P. Hamilton et al. eds., 1999), 246 (1999) [hereinafter Ameli, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal]. No particular arrangement was made for paying successful Iranian claimants and counterclaimants, who occasionally had to enforce their awards in the U.S.13

Based on these numbers, it might seem that the U.S. and its nationals were the winners before the Tribunal—and indeed, many commentators have concluded as much. For instance, Judge Brower explained the willingness of Iran to challenge judges given the State’s numerous losses:

[T]he Iranians have become very discouraged when they keep losing, losing, and losing, that’s all about, but they don’t take well to it, which is the reason for all of these challenges [to other judges.]14Remarks of Charles N. Brower, Plenary Keynote: Decision making in International Courts and Tribunals: A Conversation with Leading Judges and Arbitrators, 105 PROCEEDINGS ANN. MEETING-AM. SOCIETY INT’L L. 215, 221 (2011) (alterations added). 14

In the same vein, a former assistant to Judge Holtzmann opined that “[i]t is not a secret that in the eighteen-year history of the Tribunal, no Iranian arbitrator has ever voted to deny the claims of an Iranian claimant (or, conversely, to award damages to a U.S. national or the United States).”15Jeffrey L. Bleich, Reflections on the Tribunal’s Waning Years, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 345, 347 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (alteration added). Part V below probes that claim and reviews its significance.15 This perception likely fed the Iranian judges’ frequent accusations of bias towards the American judges and, in their words, the “so-called ‘neutral’ arbitrators.”16See Iran v. United States, Decision No. DEC 32-A18-FT (Apr. 6, 1984), 5 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 251, 277 n. 1 (dissenting opinion by Iranian arbs.).16 Accusations of bias recur in numerous dissents authored by Iranian judges,17See, e.g., Economy Forms Corp. v. Iran et al., Award No. 55-165-1 (June 13, 1983), 3 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 42, 54 (dissenting opinion by Kashani) (“The majority carries its breach of impartiality, and its bias in favour of the Claimant, to such an extreme that in its Award it openly proceeds to make statements contrary to fact.”); Watkins Johnson Co. et al. v. Iran, Award No. 429-370-1 (Jan. 8, 1990), 22 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 257, 258 (dissenting opinion by Noori) (“The majority's findings in this Case . . . are so unjust and inequitable, and so contrary to the Contract, the law and principles of logic accepted by all mankind that I cannot concur in the Award, . . . if this arbitral Tribunal had approached the Case equitably, totally without bias and prejudice[.]”).17 with no equivalent in the opinions written by American judges.

Yet when a few points are clarified, the picture that arises from the Tribunal’s output is more balanced. First, the large majority of cases were brought by U.S. claimants or the U.S. government, on its own or on behalf of claimants for minor claims, against an Iranian party. Out of the 670 cases or groups of cases in the dataset, 579 had a U.S. claimant whereas only 89 had an Iranian claimant against the U.S. government.18It was always against the U.S. government because the full Tribunal decided (over the dissent of the three Iranian arbitrators) that it had no jurisdiction over the claims of Iran against U.S. nationals. See Iran v. United States, Decision No. DEC 1-A2-FT (Jan. 26, 1982), 1 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 101, 104.18 Even if every case had an equal chance of success with a similar expectation of gains, U.S. claimants would have gained more. An analysis of the Tribunal’s overall result should take into account this asymmetry of claims.

Second, Iran was far from losing dramatically at all turns, and it was even awarded around $1 billion in claims and counter-claims from the Tribunal.19See Ameli, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, supra note 24, at 247 (noting that “at least in monetary terms, the outcome of the Tribunal’s operation appears to have resulted in some balance between the two sides, despite controversy over a number of Tribunal awards”).19

Under the 581 documents with a Tribunal decision (awards and decisions), there are 365 victories (including partial victories) for U.S. claimants against 210 victories for Iran, on the assumption that every defeat on jurisdiction or the merits for a U.S. claimant was a win for the Islamic Republic.20Every decision on jurisdiction that left at least some claims of U.S. nationals standing was coded a “U.S. winner” because anything but a full-fledged dismissal of the claims was a defeat from Iran’s point of view. See Nils Mangard, The Interpersonal Dynamics of Decision-Making (II), in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 253, 257 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (“[Iran], I have been told, counted a case as lost if one single dollar was awarded to the American party.”) (alteration added). Not all cases were clear and some decisions were reinterpreted from defeat to victories by arbitrators. See Iran v. United States, Decision No. DEC. 62-A21-FT (May 4, 1987), 14 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 324, 334 (separate opinion by Bahrami-Ahmadi & Mostafavi).20 Counting only formal partial or final awards, the picture is even more balanced with 167 victories for U.S. claimants and 145 for Iranian defendants. The numbers are summarized in Table 1 below.

|

|

Win (all decisions) |

Win (final awards only) |

||

|

Claimant Nationality |

Iran |

U.S. |

Iran |

U.S. |

|

Iran |

26 |

60 |

9 |

23 |

|

US |

184 |

313 |

136 |

145 |

|

Total |

210 |

373 |

145 |

168 |

Table 1: Win rates

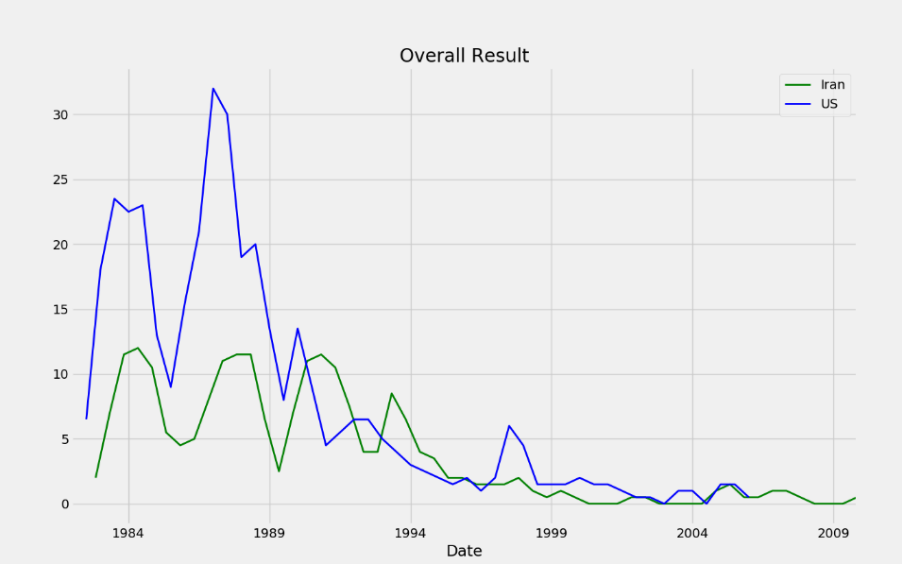

Figure 3 further retraces this distribution of outcomes over time for both groups of claimants. There were more positive outcomes for U.S. claimants at the outset because many of these decisions were interlocutory or partial awards that upheld the Tribunal’s jurisdiction—even if the case was eventually dismissed on the merits.21See, e.g., Behring Int’l Inc. v. Iran et al., Award No. 523-382-3 (Oct. 29, 1991), 27 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 219, 246 (dismissing the claims and ordering the claimant to pay Iran’s costs despite winning on jurisdiction and interim measures).21

We can delve further: not all loses carry the same weight. The more “political” claims between the two governments (“B” cases) or the cases on the interpretation of the Algiers Accords (“A” cases), for instance, were presumably more likely to sting. Yet, I find that the Iranian government lost (on the whole) 49 of the 68 decisions in B and A cases, and only won in 19 other cases.

These considerations suggest that the Tribunal’s experience has not been entirely negative for Iran.22Likewise, see T Schultz and E Dupont, ‘Investment Arbitration: Promoting the Rule of Law or Over-empowering Investors? A Quantitative Empirical Study’ (2014) 25 European Journal of International Law 4: “[…] findings [about winning rates] would say strictly nothing about any perception of bias, which is a different question altogether […].”22 Despite some high-profile cases and important defeats for Iran on the interpretation of the Algiers Accords, and more than $2 billion in compensation (mostly from settlements), the figure that emerges from the Tribunal’s jurisprudence is more balanced than a simple win rate would suggest.

The same discrepancy between perceptions and reality can be found in investment arbitration today. There are stakeholders arguing that the system favors investors, but a sober review of the facts suggests a more balanced picture. To a larger extent even than the IUSCT, investment arbitration is asymmetrical23Id. (“[Respondent states] are the claimant in less than 1 per cent of the claims and accordingly we consider such situations to be statistically irrelevant.”) (alteration added).23 such that a win rate of 50% for each party should not be treated as a proper benchmark. Pointing out that asymmetry makes things worse because states can only “not lose,” as many do, is nothing more than a talking point—it has no bearing on the question of whether individual tribunals are set to decide in favor of one particular party.24With respect to investment arbitration, commentators have tried to change the picture of overall balanced outcomes between states and investors by discounting disputes won on jurisdictional objections, see, e.g., Howard Mann, ISDS: Who Wins More, Investors or States?, International Institute for Sustainable Development at [1] (2015), but this is misleading because winning on jurisdiction is still a “win.”24

The Tribunal set an important precedent for establishing that an asymmetrical dispute-settlement system can work well25The Tribunal had predecessors in the mixed claims commissions that started in the 19th century.25 despite occasional tensions between its judges.

The Tribunal

Judges

Nine judges sit on the Tribunal. Three are appointed by the U.S., three by Iran, and the last three are “third-country judges.”1See Claims Settlement Declaration, supra note 1, art. III(1).1

|

U.S. Judges |

Third-party Judges |

Iranian Judges |

|||

|

Name |

Chamber |

Name |

Chamber |

Name |

Chamber |

|

Salans |

III |

Arangio-Ruiz |

III |

Enayat |

III |

|

Holtzmann |

I |

Bellet |

II |

Sani |

III |

|

Allison |

III |

Riphagen |

II |

Shafeiei |

II |

|

Duncan |

I |

Mangard |

III |

Kashani |

I |

|

Mosk |

III |

Virally |

III |

Ahmadi |

II |

|

Aldrich |

II |

Lagergren |

I |

Mostafavi |

I |

|

Brower |

III |

Briner |

II |

Khalilian |

II |

|

McDonald |

I |

Ruda |

II |

Ansari |

III |

|

|

Böckstiegel |

I |

Noori |

I |

|

|

Broms |

I |

Aghahosseini |

III |

||

|

Skubiszewski |

II |

Ameli |

I |

||

|

|

Yazdi |

II |

|||

Table 2: List of judges 1981-2009

There were fewer U.S. judges than Iranian judges over the Tribunal’s lifespan, which is explained by their longer average term on the Tribunal.2With an end date of July 17, 2009 (date of the last decision in the dataset), U.S. judges had an average of 5,619 days on the Tribunal, against 3,700 for third-country judges and 2,763 days for Iranian judges.2 The U.S. judges (more than double the Iranians’ average stay)—and thus, perhaps, a more central place when it comes to their influence “on the ground”; since they participated in more proceedings and sat with more co-judges than the others.

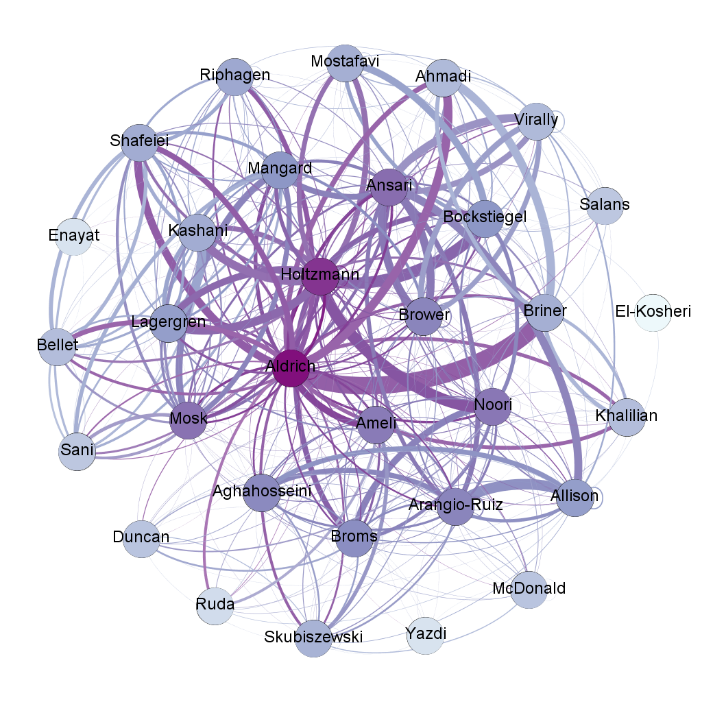

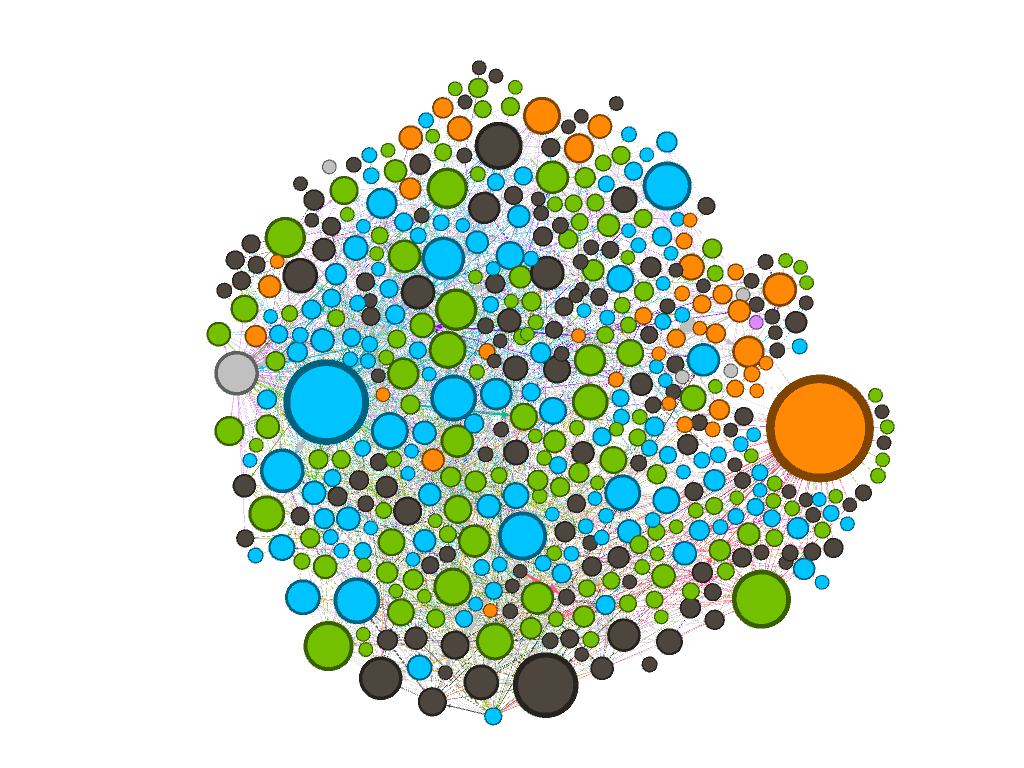

A network analysis reveals which judges were central to the Tribunal’s work based on how often they were hearing a case. Figure 4 reproduces this analysis with nodes colored according to their connections with other nodes.

The algorithm behind Figure 4 puts the more important individuals based on connections in the center, placing more marginal ones outward. As expected, the U.S. judges have stronger links with co-judges. At any point, parties were more likely to encounter the same U.S. judge who could draw from broader experience on the Tribunal.4Until the appointment of Judge Gabrielle McDonald in 2001, there were only male judges on the tribunal. Aldrich recounts that the American delegation in 1981 would not propose female third-party judges over the objections of the Iranian judges. Aldrich, supra note 17, at 68.4

Chambers

As contemplated in the Algiers Accords, the President of the Tribunal split his eight colleagues into three chambers with semi-random case assignments. Each chamber was composed of an Iran-appointed judge, a U.S.-appointed judge, and a third-country judge as chair. Because of complicated arrangements, departures, recusals, etc., however, many party-appointed judges sat on panels different from the one originally designated. Third-country judges, by contrast, could not move because they chaired the panels.

The division into chambers could have occasioned problems in at least two respects. First, it could affect the outcomes of the cases depending on the inclinations of the chair to side with either the U.S. or Iranian judge.5Clagett, supra note 18, at 63 n. 24 (“Iran has chosen its candidates [for third-party judge] skilfully; they proved disastrous for claimants unlucky enough to have cases in their chambers.”).5 In practice, however, the outcomes varied little between chambers, which treated nearly equal number of cases:6The sums awarded also did not differ dramatically once we account for the fact that different cases have different expectations of gains. In total, Chamber I awarded $132 million to American claimants and $20 million to Iranian claimants and counterclaimants; Chamber II awarded respectively $144 million and $12 million; and Chamber III respectively $246 and $7 million in compensation.6

|

Overall Result |

Majority Awards |

Unanimous Awards |

All awards |

|

CHAMBER ONE |

91 |

84 |

175 |

|

Iran |

20 |

44 |

64 |

|

U.S. |

71 |

40 |

111 |

|

CHAMBER THREE |

108 |

68 |

176 |

|

Iran |

22 |

37 |

59 |

|

U.S. |

86 |

31 |

117 |

|

CHAMBER TWO |

77 |

96 |

173 |

|

Iran |

13 |

59 |

72 |

|

U.S. |

64 |

37 |

101 |

|

FULL TRIBUNAL |

44 |

13 |

57 |

|

Iran |

7 |

7 |

14 |

|

U.S. |

37 |

6 |

43 |

|

Total |

320 |

261 |

581 |

Table 3: Outcomes per Chamber

Looking at the figures of each individual chair, two deviate from the general pattern and saw U.S. claimants win less than 2/3 of the disputes. With Judges Broms and Ruda, Iranian claimants prevailed in 2/3 of the decisions.

|

|

Winning side |

||||

|

Iran |

U.S. |

Total |

|||

|

Chair |

Count |

Percentage |

Count |

Percentage |

|

|

Bellet |

10 |

37.04% |

17 |

62.96% |

27 |

|

Bockstiegel |

21 |

23.60% |

68 |

76.40% |

89 |

|

Briner |

37 |

42.05% |

51 |

57.95% |

88 |

|

Broms |

29 |

67.44% |

14 |

32.56% |

43 |

|

Lagergren |

18 |

23.08% |

60 |

76.92% |

78 |

|

Mangard |

18 |

28.13% |

46 |

71.88% |

64 |

|

Riphagen |

8 |

38.10% |

13 |

61.90% |

21 |

|

Ruda |

14 |

66.67% |

7 |

33.33% |

21 |

|

Ruiz |

27 |

42.86% |

36 |

57.14% |

63 |

|

Skubiszewski |

9 |

30.00% |

21 |

70.00% |

30 |

|

Virally |

14 |

28.57% |

35 |

71.43% |

49 |

|

Total |

205 |

35.78% |

368 |

64.22% |

573 |

Table 4: Outcomes per Chair

These numbers should not be over-interpreted: Judge Ruda, for instance, chaired the fewest number of cases,7Aldrich surmised that Mr. Ruda left the tribunal prematurely after being subject to the “pervasive Iranian tactics of verbal and psychological abuse.” Aldrich, supra note 17, at 72.7 and he favored Iran overall with 14 unanimous decisions. Meanwhile, 19 of Mr. Brom’s decisions in favor of Iran were unanimous. Further, while Judges Broms and Ruda were among those who least found for U.S. claimants, they also did not award great sums to Iranian parties. Mr. Ruda actually never awarded any sum to an Iranian claimant or counterclaimant.

Moreover, the precedential value of the Tribunal’s awards might have been less than what it would have been had the awards been rendered by the full Tribunal, as the Tribunal’s jurisprudence could have fragmented between the different chambers.8A similar point was made about the ICJ and its ad hoc chamber procedure. See Mohamed Shahabuddeen, Precedent in the World Court 171 (2008).8

A network analysis of all citations in the Tribunal’s jurisprudence shows that this was not the case. Figure 5 below displays every citation between the Tribunal’s awards and decisions, represented as nodes of varying size9Node size depends on the number of incoming citations to a given node.9 and color according to the issuing chamber.10Chamber I’s decisions are blue, II’s are green, and III’s are black; the full Tribunal’s awards and decisions are orange.10 The algorithm places groups of decisions that mostly cite themselves out towards the edge.

Figure 5 shows that there is no coherent block of decisions by chamber that only cite themselves. Except with the Tribunal’s decision on dual national claims (the large orange node on the left), decisions by the full Tribunal were not central to the Tribunal’s jurisprudence.

Counsel

Finally, this section turns to those who appeared as counsel before the Tribunal. Counting every appearance, more than 1,300 advocates appeared on behalf of U.S. claimants, against 241 for Iranian respondents. This proved important. The Tribunal was one of the first international bodies before which a large number of private law advocates, often unfamiliar with arbitration, came to plead—and in the process many became international arbitration practitioners.11See James Crawford, The International Law Bar, in International Law as a Profession 338, 342 (Jean d’Aspremont et al. eds., 2017).11 Likewise, another commentator stated that the Tribunal’s “long twilight” proved to be “a rare training ground for young attorneys who wish to participate meaningfully in the making of decisional, international law” and that “the Tribunal’s twilight has expanded the ranks of international arbitration-trained attorneys who will hopefully contribute to this field in the future.”12Bleich, supra note 26, at 352.12

Many of today’s regulars of international arbitration have engaged with the Tribunal on behalf of a party or as a judge or clerk. Out of a list of today’s 170 most frequently appointed investment arbitrators,13This is Investment Arbitration Reporter’s list of arbitrators where only individuals with three or more appointments to an investment tribunal are included. Arbitrator Profiles, IA Reporter, https://www.iareporter.com/arbitrator-profiles-directory/.13 more than 20 have crossed the Tribunal’s path in some capacity.14This is likely underestimated because the names of the Tribunal’s clerks do not appear in the dataset, which records only the judges and counsel present at the hearing.14

Concurrences and Dissents

A striking aspect of Figure 1: Full dataset is the number of concurring and dissenting opinions written by the judges. For every three decisions by the Tribunal (including awards, orders, etc.), the dataset has two separate opinions by judges in their individual or joint capacity.1Lack of consistency in the titles and designation of opinions (many are only described as “Separate Opinion”), and the fact that some opinions dissent only in part means that the opinion labels are not clear. The difficulty was noted by the first President of the Tribunal. Lagergren, supra note 2, at 31 (“And, indeed, many opinions labelled ‘concurring’ are in reality dissenting opinions.” Cf. ITT Indus. Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 47-156-2 (May 26, 1983), 2 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 356, 357 (note by Shafeiei) (“On principle, a ‘concurring opinion’ applies when one member of the Tribunal concurs with the other members of the Tribunal in regard to the conclusion arrived at, but does not concur with its reasoning.”).1

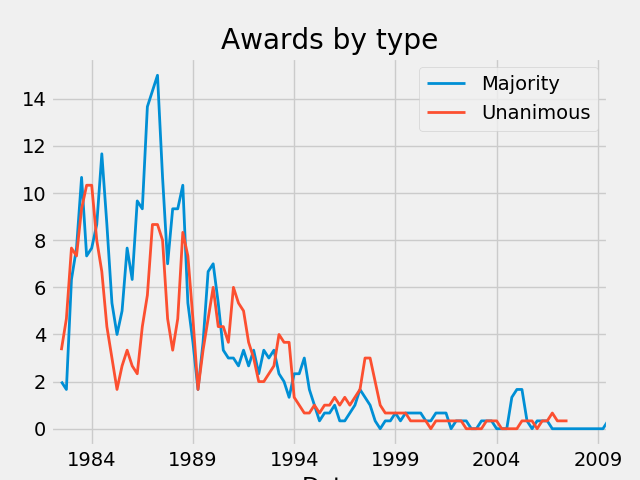

This number however only accounts for fully written opinions. Not all concurrences and dissents were written, and statements of dissent recorded under the judge’s signature at the end of the award were sometimes the only indication that an award was not adopted unanimously.2See Lagergren, supra note 2, at 28 (suggesting that judges “failed to develop a genuine sense of collegiality”).2 When all these dissents (accompanied or not by an opinion) are tallied up, there were nearly more decisions with dissents than unanimous decisions. Of the decisions on jurisdiction and the merits, 259 were unanimous (of which 92 occasioned a concurrence) while 322 were accompanied by a dissent. Figure 6 below plots the number of unanimous and majority decisions over time.

Table 5 further breaks down separate opinions according to the nationality of the judges (rare opinions by neutral judges are omitted) and the outcome of the case to reveal who dissented in what circumstances.

|

Overall Result |

# Docs (awards only) |

Concurrences |

Dissents |

||

|

U.S. arb. |

Iran arb. |

U.S. arb. |

Iran arb. |

||

|

U.S. |

373 (167) |

46 (28) |

27 (3) |

49 (40) |

263 (150) |

|

Iran |

210 (145) |

9 (4) |

70 (55) |

47 (36) |

28 (12) |

|

Total |

581 (312) |

55 (32) |

97 (58) |

96 (76) |

291 (162) |

Table 5: Concurrences and dissents per judge nationality and overall outcome

These numbers support the observation that “[i]n practice, the Iranian members recorded a dissenting vote in virtually every case in which the decision was against Iran.”3Howard M. Holtzmann, Drafting the Tribunal Rules, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 75, 91 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (alteration added).3 Indeed, when it came to final awards, only 17 cases saw no dissent from the Iranian judge—and often in cases when the respondent was not the Iranian government (typically, a US respondent),4Iran Touring & Tourism Org. v. United States, Award No. 347-B63-3 (Feb. 25, 1988), 18 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 84, 87.4 or when the outcome was such that, even if Iran lost, it was on terms broadly favorable to it.5Schering Corp. v. Iran, Award No. 122-38-3 (Apr. 13, 1984), 5 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 361, 375 (dissenting opinion by Mosk) (clarifying that Iran’s liability was very limited compared to the original claims).5

Role of individual opinions

Why write a dissenting opinion?6See generally Albert Jan van den Berg, Dissenting Opinions by Party-Appointed Arbitrators in Investment Arbitration, in Looking to the Future 821 (Mahnoush Arsanjani et al. eds., 2010).6 It was not necessarily to influence the majority decision because it was common for judges to file their dissent after, sometimes much after, the award was rendered.7See, e.g., Watkins Johnson et al. v. Iran et al., Award No. 429-370-1 (July 27, 1989), 22 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 257, 257 (dissenting opinion by Noori) (filed on Jan. 8, 1990).7 Judges might rather have wanted to influence future awards and decisions8See Parviz Ansari Moin, The Interpersonal Dynamics of Decision-Making (III), in Drafting the Tribunal Rules, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 263, 266 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (describing some opinions as “putting psychological pressure on the panel and paving the way for the next cases and awards”); see also Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 661 (explaining how the existence of third-country judges created “predictable dynamic, namely competition for the ‘hearts and mind’ of” these judges and asserting that “[w]here the vast bulk of claims is asserted against one side, namely Iran, clearly it is the Iranian side that must display the greater concern as regards the attitude of the third-country judges”).8 or to undermine the authority of a solution for later panels.9See Lagergren, supra note 2, at 31 (“However, the authority of the awards is limited by the fact that the awards mostly are accompanied by forceful dissenting and concurring opinions. . . . Accordingly, care must be exercised in concluding from the Tribunal’s awards that an opinio juris commune’s is emerging.”).9 Some judges explicitly described opinions as strategic tools10See ITT Indus. Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 47-156-2 (May 26, 1983), 2 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 356, 357 (note by Shafeiei) (“Instead, the fact is that Mr. Aldrich proceeded to state his opinions on the merits under the guise of submitting a ‘Concurring Opinion,’ and that he thereby condemned the Respondent in favour of the American Claimant. There, Mr. Aldrich gives his opinion on such issues as expropriation, control and the method of valuation, all which are matters at issue in other cases. This act is in violation of the interests and defences of the Respondent, and in fact constitutes prejudgement.).10 because they were conscious that the Tribunal was setting precedent.11Peter D. Trooboff, Settlements, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 283, 297 (David Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (“One point is clear – the Iranians were acutely sensitive to the precedent that would be set by an averse Tribunal award in certain key cases including those involving the legal principles governing expropriation and breach or [sic] contract. It seems clear, as Judge Aldrich’s ITT concurrence emphasizes, that some settlements that occurred late in the proceedings resulted from an Iranian effort to avoid the issuance of such precedent-setting awards.”).11

Some separate opinions are telling here. Judge Khalilian wrote in his dissent referring to the majority decision, “in light of the blatant defects therein, . . . it will not be possible to rely upon this Award as precedent.”12Phillips Petroleum Co. Iran v. Iran, Award No. 425-39-2 (June 29, 1989), 21 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 79, 196 (statement by Khalilian).12 Judge Bahrami once opined that he “would hope that such an award which is, as set forth above in this Opinion, devoid of legal reasoning and legal justification, will not be held up as a precedent in the Tribunal's future proceedings.”13Gen. Dynamics Tel. Syst. Ctr. Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 192-285-2 (Oct. 4, 1985), 9 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 153, 180 (dissenting opinion by Bahrami).13

This approach might however actually backfire. Providing the majority of the Tribunal is mindful of the persuasiveness of its approach and decision, an award that prompts a contemporaneous dissenting opinion might actually be better reasoned in order to answer the dissent’s criticism.14See Baker & Davis, supra note 2, at 154.14

One way to test this proposition is to observe the importance of awards based on how many times they were cited in subsequent decisions. This reveals that majority awards were cited nearly twice as often in subsequent awards and nearly four times as often when counting subsequent citations in separate opinions. The very award that Judge Khalilian hoped would not be seen as a precedent eventually became one of the most cited by the Tribunal in later awards. Majority awards are also nearly three times longer than unanimous awards, reaching 9,500 words on average compared to 3,500 words for unanimous awards, which might explain why they were relied on more.15This accords with what can be observed at the United States Supreme Court and Federal Court of Appeals. See Lee Epstein, William M. Landes, & Richard A. Posner, Why (and When) Judges Dissent: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, 3 J. Legal Analysis 101, 103 (2011).15

The direct impact of separate opinions on a given debate is likely limited because separate opinions are rarely cited in later awards.16The same occurs in the American judicial context. Id.16 The dissent of Judge Lagergren, the neutral judge and Tribunal chair in INA Corp. v. Iran, is cited, for instance, in Sedco Inc. v. National Iranian Oil Co., but only to suggest that the proper compensation standard for expropriation was not firmly established. Tellingly, when it was cited in Philipps Petroleum Co. v. Iran, it was followed shortly by Judge Holtzmann’s concurring opinion criticizing Lagergren’s views as obiter dicta.17It was not, however, that the Tribunal shied away from citing separate opinions as proper authority because individual judges at the ICJ were sometimes cited in awards. See, e.g., Bank Markazi Iran v. Fed. Reserve Bank of New York, Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib., Award No. 595-823-3 (Nov. 16, 1999), 26 Y.B. Com Arb. 689, 670-71 (2001) (quoting Barcelona Traction, Light & Power Co. (Belg. v. Spain), Preliminary Objections, 1964 I.C.J. Rep. 6, 99 (July 24) (dissenting opinion by Morelli, J.)).17 Likewise, today’s individual opinions in investment arbitration are rarely cited.18See van den Berg, supra note 58, at 826.18

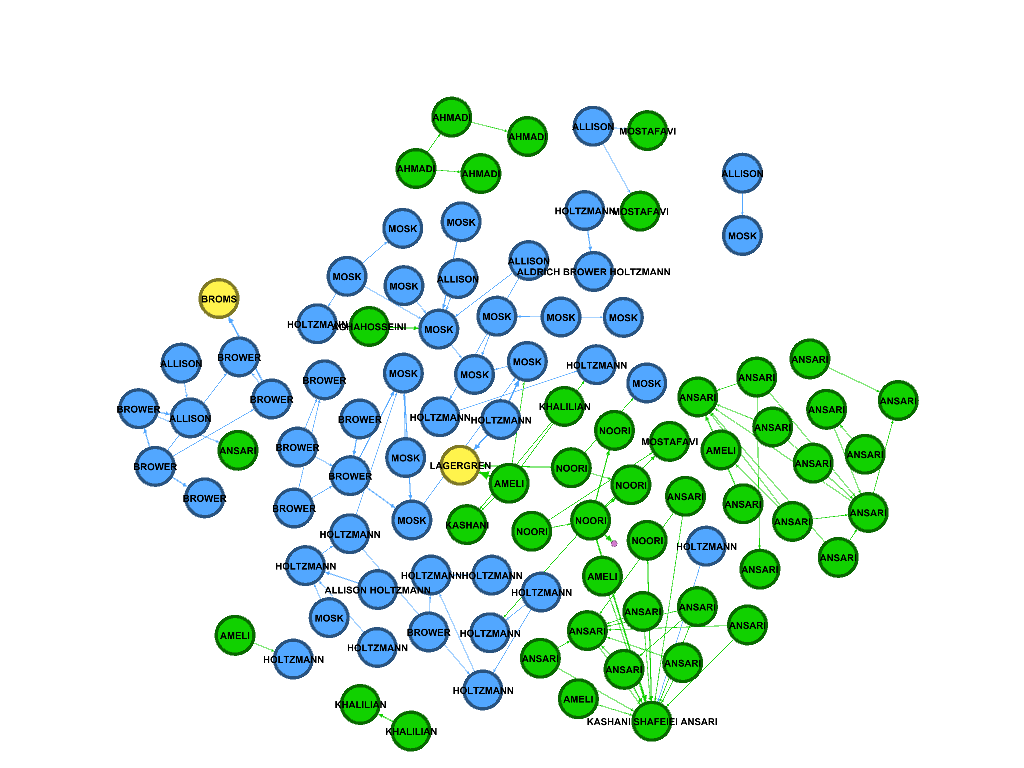

Concurrences and dissents had greater importance in other separate opinions, although party-appointed judges were more likely to cite judges from their side. This is reflected in Figure 7 below, which retraces all the citations from one judge (individually and in joint opinions), to another.19Each node represents a separate opinion. Green nodes are opinions from Iranian judges, blue from American judges, and yellow from neutral judges.19 There were few opinions by neutral judges and fewer were cited later, although Judge Lagergren’s opinion in INA Corp. became a focus of debate for both U.S. and Iranian judges as can be observed from its central position in Figure 7.

On the face of it, there was surprisingly little engagement between the two sides, which tended to rely on judges of their own nationality in their opinions. And many dissents resorted to broad disagreements between the Iranian and U.S. blocs.

The clearest example is with dual national claims, which were allowed following the full Tribunal’s decision in Case No. A18 and which “generated tremendous controversy.”20Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 32.20 In a strong dissent, the Iranian judge condemned the notion of allowing Iranian nationals (albeit dual nationals) to bring claims against their own government,21In an important point of background, Caron & Crook, The Tribunal at Work, supra note 13, at 141, opines that the Iranian judges also suspected that many dual nationals were from powerful and well-connected families that had supported the deposed Shah.21 and they often voiced their opposition thereafter.22See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 296 (calling it a continuous “source of acrimony” and citing, e.g., Golshani v. Iran, Award No. ITL 72-812-3 (Oct. 24, 1989), 22 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 155, 160 (dissenting opinion by Ansari)); see also Mohsen Aghahosseini, Claims of Dual Nationals and the Development of Customary International Law: Issues Before the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal 33 (2007) (“Of all the cases litigated before the Tribunal, and those include Cases in which giant multi-national oil companies sued Iran for hundreds of millions of dollars, none was so hotly and passionately contested as this interpretative Case between the two States.”). No case was brought by a dual national against the U.S. government.22 The decision is often offered as a reason for the “Mangard incident” mentioned above in Part I.

The strength of this dissent, however, means that what became known as “The dissent of the Iranian judge in Case No. A18 was the opinion most cited by other opinions (17 times), even long after the decision on dual national claims was taken. The Iranian judge continuously found against jurisdictional decisions involving dual nationals,23See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 41-42 (“Because the Tribunal’s analysis is a fact intensive inquiry into what is largely a subjective and emotional belief on the part of the claimant, its conclusions have frequently divided the Members of the Chambers. The Iranian Members of the Tribunal, in fact, regularly dissent from the finding of dominant and effective United States nationality, evidencing what appears to be continuing dissatisfaction with the Full Tribunal’s decisions in Case No. A18.”).23 and given the sensitivity of the issue, many of the claims were postponed until the 1990s.24See Zenkiewicz, supra note 13, at 159 n. 37.24

Tone

A final aspect of the separate opinions to investigate is the tone adopted by the judges. Acrimony has permeated the Tribunal, which is evinced by the fact that “[u]nanimous decisions were rare in contested cases and the awards were usually accompanied by aggressively drafted dissenting opinions.”25See Mangard, supra note 31, at 255 (alteration added).25

Aggressiveness is a factor that can be measured by performing a sentiment analysis, which ranks text based on how relatively positive or negative it is. Dissents presumably should be more negative in tone than concurrences, which are expected to be more positive than majority decisions.

A sentiment analysis was performed over the first 500 characters of every concurring and dissenting opinion with the hypothesis that the introduction would better reveal the sentiments of the judge authoring the opinion. While sentiment analyses as applied to long texts are usually less instructive than for sentence long texts, the difference in mean scores between the categories of texts remains instructive. The results can be seen below in Table 6. As expected, dissents, and notably dissents by Iranian judges, were much more negative than other separate opinions.26The differences between the mean score of the set of dissenting opinions is statistically significant. The survey had a t-score of 2.5 and a p-value of 0.01.26 To the extent that these opinions were strategically used to undermine the precedential value of a given decision, it is unclear whether more negativity was a winning strategy.27Instead, these findings might indicate that opinions from Iranian judges were directed at a different audience, e.g., domestic interests in Iran. See Richard M. Mosk, The Role of Party-Appointed Arbitrators in International Arbitration: The Experience of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, 1 Transnat’l Law. 253, 268 (1988) (suggesting that Iranian judges were scrutinized for their actions by their government).27

|

|

Dissenting |

Concurring |

|

Iranian judge |

0.029 |

0.051 |

|

U.S. judge |

0.056 |

0.112 |

Table 6: Average sentiment score

Sources

Separate opinions also differed starkly on the sources cited for arguing their point of view. An overview of all the sources cited in awards and separate opinions indicates that separate opinions cited the Tribunal’s precedents markedly less than in majority and unanimous decisions. Concurring opinions in particular drew from a varied pool of resources.

This presumably stems from a different need to persuade. Concurring opinions were seemingly less constrained and the authors were free to discuss sources with less authority, while dissenting opinions focused more on proper precedent to highlight contradictions in the Tribunal’s jurisprudence.

|

Citation Target |

Concurring |

Dissenting |

Award |

|

Tribunal’s Precedents |

37.5 |

63.6 |

85.3 |

|

Doctrinal Sources |

26.0 |

15.5 |

4.5 |

|

ICJ |

11.6 |

8.4 |

3.2 |

|

Other Awards |

14.3 |

6.8 |

2.6 |

|

Domestic Judgment |

5.3 |

2.6 |

1.3 |

|

Positive Law |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

|

ICSID |

3.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

|

ECHR |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

Table 6: Sources cited by type of document, percent

The judges were also likely to cite different sources depending on their nationality as shown in Table 7. Iranian judges, for instance, were unlikely to cite jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This is perhaps unsurprising given that in the mid-1980s, the Court’s reputation with non-Western states had reached a nadir. U.S. judges, conversely, have been more familiar with or have tended to rely more on decisions by tribunals of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), which might also be because some of the U.S. judges were themselves involved in those disputes.28Judge Brower, for instance, had been counsel for Indonesia in the long-running arbitration of Amco Asia Corp. et al. v. Republic of Indonesia, ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1.28

|

Citation Target |

Iran |

Neutral |

U.S. |

|

Tribunal’s Precedents |

60.9 |

28.6 |

57.3 |

|

Doctrinal Sources |

16.4 |

28.6 |

18.8 |

|

ICJ |

9.7 |

23.8 |

8.2 |

|

Other Awards |

7.4 |

9.5 |

7.7 |

|

Domestic Judgment |

2.2 |

4.8 |

4.2 |

|

Positive Law |

2.2 |

/ |

2.4 |

|

ICSID |

0.6 |

/ |

1.2 |

|

ECHR |

0.5 |

4.8 |

0.1 |

Table 7: Sources cited by Judge's nationality, percent29The numbers for neutral judges should be qualified by the fact that individual opinions by these judges are scant. Interestingly, the proportion of scholarly sources found in awards matches those found in other contexts. See Nora Stappert, A New Influence of Legal Scholars? The Use of Academic Writings at International Criminal Courts and Tribunals, 31 Leiden J. Int’l L. 963, 971-972 (2018).29

Subjects and Topics

The limited scope of the Algiers Accords means that only a limited set of disputes went before the Tribunal and thus the judges have often faced the same questions.1See, e.g., Zenkiewicz, supra note 13, at 154 (identifying three categories of claims). 1

To shed light on this, an analysis was performed that identified sets of words and phrases that commonly occur together and at significant rates across the dataset, indicating a distinct topic. The analysis identified 30 core topics, which are listed in Table 8 below.2Several topics identified by the algorithm were very closely related to particular cases and I discounted them as “Other.” The search for topics in individual documents later ignored these “Other” topics to focus on the next most important topic.2 Next, each document (award, opinion, etc.) was reviewed at the paragraph level for these topics to detect the most important of the 30 topics.3More precisely, the analysis is probabilistic, with every document having a probability of “x” of dealing with a given topic “y.” The analysis only retained the topics that were above a certain significant probability threshold. Only paragraphs with a citation were parsed to filter out fact-heavy paragraphs and focus on legal topics.3 The analysis relied on the number of times these topics appeared in the Tribunal’s documents to gauge their relative importance.

In awards and decisions

Unsurprisingly, the major topics discussed in awards and decisions align with the topics of scholarly works.4See, generally, Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2.4 The analysis confirms that chambers were often tasked with verifying their jurisdiction over claimants and, following a decision by the full Tribunal on dual national claims, with the dominant nationality of U.S. claimants. On the merits, the Tribunal heard many contract-based cases and counterclaims, and the occasional argument on expropriation. Claims brought by Iranian claimants often focused on principles (A) and (B) of the Accords.5Principle (A) obliged the U.S. to restore the financial position of Iran as it was prior to the diplomatic break, while Principle (B) mandated the termination of all external litigation between the parties and their nationals.5

The analysis confirms that the prevalence of the topics varied over time. Looking at the topic “oil,” for example, which refers to disputes over oil reserves, productions, etc., indicates that it peaked in early disputes, especially in 1990, when Philips Petroleum was decided. The fraught topic of dual national claims peaked in April 1984 when the full Tribunal ruled on its jurisdiction over those claims and then became sporadic before rising again in the 1990s as if the Tribunal had decided to defer the claims until tensions abated—which is exactly what happened according to most commentators.6Cf. David D. Caron & John R. Crook, Moving to End Game, in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 331, 335 (David D. Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000) (“Following the events of 1984, arbitrators were not inclined to push the dual national cases forward rapidly.”).6

In opinions

With some exceptions, concurrences and dissents often focused on more abstract questions of interpretation, jurisdiction, and, in particular, applicable law. While topics like contract, ownership, and counterclaims were among the main matters discussed in the awards themselves, they came up at lower rates in dissents and rarely in concurrences.

Table 8 retraces the total number of topics in concurrences, dissents, and awards, as well as the rate of separate opinions treating a given topic compared to awards—giving an idea of their importance for individual judges. For instance, questions of unjust enrichment surfaced nearly half as much in dissents as in awards, but barely in concurring opinions.

|

Topic |

Concurrence |

Dissent |

Award |

Concurrence Rate |

Dissent Rate |

|

Jurisdiction |

54 |

108 |

720 |

7.50 |

15.00 |

|

Procedure |

23 |

69 |

430 |

5.35 |

16.05 |

|

Counterclaims |

17 |

59 |

422 |

4.03 |

13.98 |

|

Contract |

25 |

85 |

372 |

6.72 |

22.85 |

|

Ownership |

14 |

40 |

347 |

4.03 |

11.53 |

|

Evidence |

23 |

135 |

299 |

7.69 |

45.15 |

|

Interpretation |

95 |

170 |

233 |

40.77 |

72.96 |

|

Control |

15 |

50 |

188 |

7.98 |

26.60 |

|

Dual Nationality |

14 |

43 |

180 |

7.78 |

23.89 |

|

Banking |

28 |

46 |

164 |

17.07 |

28.05 |

|

Choice of Forum |

14 |

32 |

156 |

8.97 |

20.51 |

|

Force Majeure |

15 |

68 |

152 |

9.87 |

44.74 |

|

Interests |

39 |

48 |

127 |

30.71 |

37.80 |

|

Principle B |

30 |

32 |

121 |

24.79 |

26.45 |

|

Expropriation |

11 |

24 |

112 |

9.82 |

21.43 |

|

Interim |

13 |

20 |

110 |

11.82 |

18.18 |

|

Request |

1 |

10 |

109 |

0.92 |

9.17 |

|

Transfers |

6 |

39 |

90 |

6.67 |

43.33 |

|

Caveat |

8 |

27 |

79 |

10.13 |

34.18 |

|

Applicable Law |

41 |

52 |

71 |

57.75 |

73.24 |

|

Quantum |

8 |

13 |

70 |

11.43 |

18.57 |

|

Unjust Enrichment |

4 |

28 |

59 |

6.78 |

47.46 |

|

Standard |

15 |

17 |

59 |

25.42 |

28.81 |

|

Award |

25 |

9 |

39 |

64.10 |

23.08 |

|

Signature |

11 |

13 |

37 |

29.73 |

35.14 |

|

Nationality |

1 |

14 |

34 |

2.94 |

41.18 |

|

Principle A |

4 |

10 |

32 |

12.50 |

31.25 |

|

Litigation |

2 |

13 |

27 |

7.41 |

48.15 |

|

Challenge |

14 |

6 |

26 |

53.85 |

23.08 |

|

Oil |

2 |

0 |

9 |

22.22 |

0.00 |

|

Authenticity |

4 |

5 |

4 |

100.00 |

125.00 |

Table 8: Topics, number of observations, and as a ratio of observations in awards

Dissents often discussed questions of evidence, which is not surprising. The Tribunal never formally identified a standard of proof,7Koorosh H. Ameli, The Application of the Rules of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, in International Law and The Hague’s 750th Anniversary 263, 272 (Wybo P. Heere ed., 1999) (“In various cases, the Tribunal has simply concluded from its interpretation of the evidence what in its view should be the fact, without reference to any standard of proof and justifications for it. Thus, an independent examination of the evidence, even as presented in some of the awards, may allow a different conclusion from what the award has reached.”).7 so judges had some discretion in assessing the evidence. Judge Mangard opined that U.S. judges often dissented on this point when stricter European standards were applied.8Mangard, supra note 31, at 259; and see generally Anna Riddell & Brendan Plant, Evidence Before the International Court of Justice (2009). 8 Judge Brower echoed this point, adding that evidential matters left room for the third-country judges to “give in” in the context of always “saying no” to Iran.9See Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 662 (“Further up the line, decisions may be made on evidentiary issues or regarding damages that legitimately might have been decided either way.”). In the same context, Judge Brower also contends that the president in his first full Tribunal case voted with the Iranians only after being sure to be in the minority. See Mangard, supra note 31, at 259.9 All this gave judges space to write dissenting opinions on evidence questions.

Interest in topics also differed depending on the author’s nationality:

|

Iran |

U.S. |

||||||

|

Concurring |

Dissenting |

Concurring |

Dissenting |

||||

|

Interest |

47 |

Interpretation |

154 |

Standard |

232 |

Evidence |

107 |

|

Unjust Enrichment |

24 |

Evidence |

149 |

Choice of Forum |

94 |

Control |

102 |

|

Award |

23 |

Dual |

131 |

Applicable Law |

83 |

Procedure |

102 |

|

Dual |

19 |

Expropriation |

103 |

Interpretation |

62 |

Interpretation |

89 |

|

Jurisdiction |

6 |

Standard |

103 |

Interests |

52 |

Nationality |

86 |

|

Control |

5 |

Principle A |

95 |

Award |

40 |

Applicable Law |

83 |

|

Counterclaims |

5 |

Jurisdiction |

92 |

Contract |

39 |

Counterclaims |

63 |

|

Choice of Forum |

4 |

Caveat |

85 |

Jurisdiction |

33 |

Request |

63 |

|

Interpretation |

4 |

Contract |

85 |

Expropriation |

32 |

Dual |

56 |

|

Principle B |

3 |

Procedure |

85 |

Control |

31 |

Ownership |

56 |

|

Applicable Law |

2 |

Control |

70 |

Interim |

24 |

Quantum |

46 |

|

Banking |

2 |

Counterclaims |

62 |

Principle B |

24 |

Force Majeure |

45 |

|

Transfers |

2 |

Force Majeure |

52 |

Banking |

19 |

Banking |

39 |

|

Challenge |

1 |

Choice of Forum |

42 |

Oil |

15 |

Transfers |

34 |

|

Procedure |

1 |

Interests |

32 |

Quantum |

15 |

Caveat |

32 |

|

|

|

Quantum |

30 |

Counterclaims |

14 |

Interests |

32 |

|

|

|

Transfers |

28 |

Procedure |

11 |

Choice of Forum |

28 |

|

|

|

Award |

27 |

Evidence |

10 |

Interim |

28 |

|

|

|

Ownership |

27 |

Ownership |

10 |

Jurisdiction |

27 |

|

|

|

Signature |

23 |

Signature |

9 |

Contract |

22 |

|

|

|

Principle B |

15 |

Force Majeure |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Applicable Law |

14 |

Caveat |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Unjust Enrichment |

12 |

Challenge |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Oil |

7 |

Litigation |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Interim |

6 |

Transfers |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Banking |

5 |

Unjust Enrichment |

1 |

|

|

Table 9: Topics, number of observations, per type and author nationality

The topic of evidence remained one of the most popular, not only in U.S. dissents but also in Iranian ones. It is noteworthy that Durward Sandifer’s book, Evidence before International Tribunals, is by far the most cited scholarly authority in the dataset even though it was cited only in separate opinions and rarely in awards.

There are however also marked discrepancies in interests depending on the judge’s nationality. Iranian dissents focused more on the topic of dual nationals that the Tribunal ruled it had jurisdiction over, which was also closely related to the issue of dual national claims.10The full Tribunal “caveated” its position on dual national claims by holding that a claimant’s dual nationality might be relevant in matters of liability or quantum.10 U.S. dissents, meanwhile, were often concerned with the topic of control, considering that the Tribunal often denied expropriation claims based on a claimant’s failure to show sufficient control of the expropriated entity. The topic of unjust enrichment, which was often an alternative claim against Iranian defendants, arose mostly in Iranian opinions and was relatively ignored by the U.S. judges.

The significance of the differing interests is examined in the next and last parts, which suggest that there were extra-legal motivations that likely motivated the judges.

Was the Tribunal Political and Does It Matter?

The numbers above shed light on one of the most fraught questions in the scholarship surrounding the Tribunal’s work, standing to undermine its importance and legacy: whether the Tribunal was political and whether this should discount its legacy.1See Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah, The Pursuit of Nationalized Property 202 (1986).1

This criticism remains relevant today as it shares much in common with a perennial debate about the role, motives, and influence of party-appointed judges in investment arbitration today.2See Waibel & Wu, supra note 18, at 8; Jan Paulsson, Moral Hazard in International Dispute Resolution, 25 ICSID Rev. 339, 339-48 (2010) (arguing that the politicization in unilateral arbitrator appointments undermines the legitimacy of arbitration).2

The charge

Some scholars suggest that the Tribunal’s awards and decisions were merely the outcome of an adjudicative body permeated by politics and tainted by each side’s motivation of winning at all costs.3See David D. Caron, The Nature of the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Evolving Structure of International Dispute Resolution, 84 Am. J. Int’l L. 104, 105 (1990); see also Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 648 (making similar criticisms); Ameli, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, supra note 24, at 246 (noting the “controversies over the precedential value of [the Tribunal’s] jurisprudence”) (alteration added). The notion that the tribunal was politicized was accepted, for example, by Judge Brower who opined that the tribunal was bound to be “politically affected” due to its structure and the circumstances of its birth. Charles N. Brower, The Interpersonal Dynamics of Arbitral Decision-Making (I), in The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal and the Process of International Claims Resolution 249, 250 (David D. Caron & John R. Crook eds., 2000).3 The background of the Tribunal’s operations informs these criticisms: relations between Iran and the U.S. have been marked by great tensions since the Iranian Revolution,4See Zenkiewicz, supra note 13, at 173 (“The relationship between those two States can be characterized as unusually tense, if not openly hostile. In that framework, especially when the only cases left were the intergovernmental disputes, the Tribunal members sensed the constant and increasing pressure to decide cases on grounds that were more political than legal.”).4 making it hard to believe the Tribunal was immune. As recounted above in Part II, accusations of impartiality have occasionally flared between the judges themselves.5See ITT Indus. Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 47-156-2 (May 26, 1983), 2 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 356, 358 (note by Shafeiei).5

Several ways to answer this charge have surfaced in the literature. First, it is sometimes pointed out that the charge is a non sequitur: the “political” outlook of the judges, if any, does not necessarily mean the solutions adopted and their reading of the law was deficient.6See Caron, supra note 98, at 105 n. 1 (“I believe the combativeness of the Iranian arbitrators did not politicize substantive decisions.”); see also Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 650 (“There would appear in any event to be natural limits to how far political considerations can, in the long run, successfully pervert a publicly carried out process of adjudication controlled ultimately by third-country nationals of high distinction.”).6

It also bears noting that the principle of coherence should function to refrain judges’ willingness to always rule in favor of a party, lest to be accused of deciding contrary to their past decisions. For some authors, the more the Tribunal became a permanent court, the more legitimate it became and the more independent it could venture to be.7See Alter, supra note 11, at 186.7

Another answer that is more common in the literature denies that the Tribunal was political and insists that judges generally worked and ruled in a professional manner, regardless of the claims before them.8Brower & Brueschke, supra note 2, at 655 (“[P]ersonalities, politics and psychological pressures have played a role in some of the Tribunal’s more difficult decisions,” but that is a “very minute group. . . . In the vast majority of cases, however, the presence of these pressures has not affected the award in any significant way. . . . [I]t is human nature that no person can bear it well to be on the losing side year in and year out. . . . Similarly, few would be comfortable in the position, potentially occupied by third-country judges of the Tribunal, of more or less continually ‘saying no’ to a party, i.e., Iran.”) (alterations added).8 Judge Mosk, for instance, said that “[g]enerally, despite diplomatic differences between Iran and the United States and some sharply worded opinions (which are not unheard of in American appellate cases), Iranian and United States representatives to the Tribunal and the arbitrators work together in a civil and courteous manner.”9Mosk, supra note 80, at 270 (suggesting that the argument itself is a non sequitur because a tribunal could be highly politicized and still remain “courteous and professional”).9

Judge Mosk observed that the U.S. judges (read: “at least”) understood that they were not supposed to be representing their government,10Id. at 267.10 and he offers several decisions where they voted against the U.S. party.11Id. at 267, nn. 49-50. Mosk notes that the American judges voted for levying a large award against the U.S., but he does not clarify whether the judges dissented from the award. Cf. Iran v. United States, Award No. 306-A15(I:G)-FT (May 4, 1987), 14 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 311, 320 (concurring opinion by Holtzmann et al.) (“This Partial Award implements an earlier Interlocutory Award in this Case from which all three American members of the Tribunal disagreed for the reasons set forth in their Dissenting Opinion.”).11 He added, diplomatically, that the Iranian judges “may have been in a more delicate situation” ascribing their difficulties to the revolutionary government at the time, and noting that they rarely voted against Iran and if so only in small cases.12Mosk, supra note 80, at 268 (“Iranian arbitrators have joined in some awards against Iran, but this occurred infrequently, and generally only when the award was substantially less than the amount claimed.”).12

Lessons from the data

The data analyzed above lends to Judge Mosk’s observation that Iranian judges largely dissented in cases won by the U.S. party. The same discrepancy can to some extent be observed in the voting pattern of the American judges.

While raw statistics should not be overstated,13This statistical approach to the question has been criticized. See Commentary by Kryzysztof Skubiszewski, The Role of ad hoc Judges, in Increasing the Effectiveness of the International Court of Justice, Proceedings of the ICJ 378, 389 (Connie Peck at al. eds., 1997) (“I am not very convinced that the statistics about voting behaviour, like statistics about the number of ratifications of treaties and similar statistical games, tell us much about the law and the real posture[.]”). But Mr. Skubiszewski’s point cuts both ways: some awards were unanimous in appearance, but that could have been, for instance, because a “losing” judge thought it was a win considering that the liability could have been higher. Nevertheless, the “statistics” themselves seemingly mattered greatly to the parties and to the tribunal. See Mangard, supra note 31, at 261.13 going beyond them confirms that the rare instances of an judge authoring a dissent when its government was broadly successful were often directed at few findings going in the direction of the losing party, who appointed that judge. Thus, if Judge Bahrami wrote a dissent in FMC Corp. v. Ministry of National Defense,14FMC Corp. v. Ministry of Nat’l Def. et al., Award No. 292-353-2 (Feb. 12, 1987), 14 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 111, 103 (dissenting opinion by Bahrami).14 where Iran’s counterclaims exceeded the value of the claimant’s claim, it was to undermine the Tribunal’s findings on the merits of the claimant’s case. On the other hand, in cases won by U.S. claimants, a substantial number of dissents by the U.S. arbitrators were actually due to Judge Holtzmann on the question of costs (of which, he opined, claimants should be able to recover a larger portion).15See, e.g., Sylvania Tech. Sys. Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 180-64-1 (June 27, 1985), 8 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 298, 329 (separate opinion by Holtzmann).15

Party-appointed judges were also more likely to dissent in high-stake decisions, but not necessarily in disputes between the two governments16But cf. Allen S. Weiner, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal: What Lies Ahead?, 6 L. & Prac. Int’l Cts. & Tribs. 89, 96 (2007) (“As the docket narrows to cases involving only two parties, Tribunal Members may perceive increasing pressure to decide cases on grounds that are more political than legal.”).16 where the proportion of dissents tracks that of other cases and with Iranian judges even agreeing to find Iran liable.17See, e.g., Iowa St. Univ. v. Ministry of Culture & Higher Ed. et al., Award No. 276-B72-2 (Dec. 16, 1986), 13 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 271, 276.17 Iranian judges dissented however in all but three of the 149 decisions that ended with a financial outcome in favor of a U.S. claimant. These were presumably higher-stake decisions because Iran reportedly disapproved of any dollar that went the American way. U.S. judges, by contrast, were more inclined to join a decision that found the U.S. government liable.

In short, virtually every separate opinion supported the side that appointed the judge. As Albert Jan van den Berg noted:

In a tribunal of three, one could imagine that there is about a 33 percent chance that the dissenting opinions would be in favor of that party; or, if one eliminates the presiding arbitrator, the chance may be about 50 percent. It is said that ‘the parties are careful to select arbitrators with views similar to theirs.’ Assuming—generously—that such a factor influences half of dissenters, the percentage could be assessed to be about 75 percent.18Van den Berg, supra note 57, at 824.18

A rate of nearly 100% indicates that something else was the matter. The pattern of dissents supports the observation that the appointment method created partiality.19See id. at 834 (“Unilateral appointments may create arbitrators who may be dependent in some way on the parties that appointed them.”).19

As seen in Part IV above, party-appointed judges created two blocks of separate opinions on which to rely and cite—blocks which were aligned with nationality. Table 10 below indicates that the U.S. and Iranian judges were slightly more likely to cite precedent that supported their appointing party, but in all cases, decisions won by the U.S. are over-cited compared to those won by Iran. As also seen in Part IV, Iranian and U.S. judges drew from different types of authorities when supporting their opinions.

|

Overall Result |

# of decisions won |

# citations in Iranian opinions |

# citations in American opinions |

# citations in awards and decisions |

|

Iran |

209 |

250 |

201 |

736 |

|

U.S. |

365 |

581 |

825 |

2783 |

|

Ratio |

0.57 |

0.43 |

0.24 |

0.26 |

Table 10: Citations of precedent by cited authority's overall winner

Part V, meanwhile, indicated how the blocks of judges had varying interests in the matters handled by the Tribunal. This is to be expected of judges from different legal systems and traditions. But the fact that some topics (e.g., dual national claims and standards of compensation) remained crucial in separate opinions long after they have, seemingly, been disposed of by an award indicates that this was more than a question of varying interests. Rather, it is hard not see there a certain motivation to relitigate past issues.

All this suggests that at least two of the three judges in a given case cared more about their nationality and the nature of the claims than the pure legal merits.

Does it matter?

Being politicized does not mean that the Tribunal’s findings were tainted. As found in Part IV above, majority decisions tended to be longer and with more citations than unanimous decisions and presumably better reasoned. The advocate attitude of the party-appointed judges might have ensured that the final outcome in the award was all the more reasoned and grounded in law.

In other words, the clear conflicts on the law between irreconcilable judges might have ensured the logical soundness of awards. Later, the precedent also constrained the margin of appreciation of future panels. Ultimately, the outcomes were relatively balanced and the political underpinnings of individual cases could not translate into a general political bias that smeared the Tribunal’s work.

The assertion that because of the appointment method judges acted based on political affinity, undermining the integrity of awards, goes too far—especially considering that appointing judges with diverging views is often the very aspect of arbitration that is appealing to disputing parties.20Waibel & Wu, supra note 8, at 4.20 The Tribunal’s experience with hundreds of awards often accompanied by separate opinions was one of balanced outcome, strengthening the merits of the system of party appointments.

Conclusion