Introduction

Investor-state dispute settlement (“ISDS”) involves intricate legal matters that intersect public international law and private law. Typically found in international investment agreements, ISDS clauses are vital for protecting the rights of foreign investors. However, challenges arise when investors lack the financial resources needed to pursue an investment claim against a state. In such cases, third-party funding has emerged as a solution to enable cash-strapped claimants to have recourse to arbitration. Third-party funding itself, however, has led to further complications for ISDS in the way of promoting frivolous claims and posing risks for respondent states in obtaining security for costs against insolvent claimants.

A central question of this article is how third-party funding, a mechanism intended to facilitate access to arbitral justice, has evolved to challenge the legitimacy of ISDS. The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Working Group III on ISDS reform is currently debating these concerns, but as of yet there are no concrete initiatives for addressing concerns with third-party funding.

Acknowledging the inadequacy of the current ISDS framework for resolving issues with third-party funding, this article employs a “law and economics” methodology to advocate for regulation through an opt-in multilateral mechanism.1Cf. Francesco Parisi, Positive, Normative and Functional Schools in Law and Economics, 18 EUR. J.L. & ECON. 259, 261-262 (2004) (explaining that law and economics, as a research methodology, “applies the conceptual apparatus and empirical methods of economics to the study of law [and] relies on the standard economic assumption that individuals are rational maximizers, and studies the role of law as a means for changing the relative prices attached to alternative individual actions”).1 Specifically, section II gives an overview of law and economics as a methodology and emphasizes its core concept of efficiency. Section III explains how third-party funding is being scrutinized by the international community, which validates the need for regulation. Section IV then proposes an opt-in multilateral instrument that enhances efficiency and concludes that regulating third-party funding is essential to maintaining the legitimacy of ISDS.

Law and Economics Methodology, an Overview

The law and economics approach has been hailed as “the greatest innovation in legal thinking at least since the code of Hammurabi,”1NICHOLAS L. GEORGAKOPOULOS, PRINCIPLES AND METHODS OF LAW AND ECONOMICS: ENHANCING NORMATIVE ANALYSIS 3 (2005).1 embodying the fruitful application of economic principles “into areas that were once regarded as beyond the realm of economic analysis and its study of explicit market transactions.”2Parisi, supra note 1, at 259.2 As a methodology, law and economics applies economic principles and methods to analyze the efficiency of legal rules that address market failures.3Id.3

In law and economics, market failure is considered the “raison d’être of law,”4Alessio M. Pacces & Louis T. Visscher, Methodology of Law and Economics at [1] (2011), available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=2259058.4 and it occurs when resources are inefficiently allocated within markets,5John O. Ledyard, Market Failure at 1, Social Science Working Paper 623, California Institute of Technology (1987), available at https://www.scribd.com/document/665115089/Market-Failure-John-O-Ledyard-1987.5 particularly when “the assumptions underpinning perfect competition fail to hold.”6Charles K. Rowley, Social Sciences and Law: The Relevance of Economic Theories, 1(3) OXFORD J. LEGAL STUDIES 391, 401 (1981).6 John Ledyard characterizes perfect competition conditions as the “[f]irst Fundamental Theorem of welfare economics,” which posits three conditions for a prosperous market: (i) “enough markets,” (ii) “all consumers and producers behave competitively,” and (iii) “an equilibrium exists [in the] allocation of resources.”7Ledyard, supra note 6, at 1.7

Under law and economics, market failure requires a framework to address and rectify inefficiencies. Efficiency is based on the “maximization of social welfare” through a cost-benefits analysis.8Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [5].8 According to Hans-Bernd Schäfer and Claus Ott, efficiency, in economic terms, means utilizing society’s “scarce and disposable resources in such a way that the highest possible degree of need satisfaction is obtained.”9HANS-BERND SCHÄFER & CLAUS OTT, THE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF CIVIL LAW 1 (2022).9

The Pareto and Kaldor-Hicks’s efficiency theories are the two main approaches to achieving efficiency in law and economics.10Parisi, supra note 1, at 266-67.10 Pareto efficiency ensures that “it is no longer possible to make one person better off without making at least one person worse off.”11Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [4].11 To better comprehend this concept, suppose there is a small community with two residents: A and B. A excels in fishing but not farming, while B is a good farmer but struggles with fishing. In an inefficient scenario, A and B attempt to carry out both activities. However, they are not as productive as they could be if they specialized in their best activity. Pareto efficiency could be achieved if A focused entirely on fishing and B on farming. They could then agree to trade a portion of their catch and crops with each other, resulting in a higher yield of fish and crops for both parties.

Conversely, Kaldor-Hicks’s efficiency deems an economic measure efficient if it results in a general increase in social welfare.12Cf. Matthew Manning, Cost-Benefit Analysis, in ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE 641, 642 (Gerben Bruinsma & David Weisburd eds., 2014) (describing Kaldor-Hicks’s efficiency as an “alternative decision rule with possibly less conceptual appeal but more practicability”).12 Pacces and Visscher explain that “[a] change is hence regarded as an improvement if the persons who benefit from the change are able to compensate those who get worse off, and still they prefer the new situation to the old one (the criterion does not require actual compensation).”13Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [5].13 Under the same hypothetical scenario developed above, imagine that A, who is focused on fishing, experiences a greater increase in utilities from trade compared to B, who is focused on farming. The Kaldor-Hicks efficient outcome could occur if a cost-benefit analysis concludes that “gains exceed losses.”14THOMAS J. MICELI, THE ECONOMIC APPROACH TO LAW 7 (3d ed. 2017). 14 Even if the gain for B is not as large as A’s, B will still experience a positive net gain, making the outcome efficient. As Alessio Pacces and Louis Visscher stated, Kaldor-Hicks does not mandate actual compensation.15Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [5]).15 Instead, the focus is on the “maximization of social welfare,” even if some individuals may experience losses.16Id. at [4].16

Practically, law and economics principles analyze legal issues by viewing individuals as “rational maximizers.”17Parisi, supra note 1, at 3, 262. 17 Legal rules are used as a means to attain wealth maximization, which Francesco Parisi identifies as the “paradigm for the analysis of law.”18Id.18 It is noteworthy that the “economic analysis of law can apply to any rule [on] the belief that individuals respond to incentives in all areas of activity.”19GEORGAKOPOULOS, supra note 2, at 30-31.19 According to Christine Jolls et al., incentives are significant when changes in costs and benefits lead to a modification in actors’ behavior in response to those changes.20Christine Jolls et al., A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics, 50 STAN. L. REV. 1471, 1488 (1998).20

Pacces and Visscher assert that in “law and economics, the economic approach operates on two distinct levels.”21Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [1].21 The first level entails analyzing human choice, with the most common approach being the “rational choice theory.”22Id.22 This is a well-known principle of economics that posits that individuals act to maximize their expected utility.23Id.23 The authors suggest that any rational decision has three elements: (i) the decision-maker’s preferences, (ii) the decision-maker’s expectations based on available information, and (iii) the decision-maker’s satisfaction with the information obtained.24Id. at [2].24 This decision-making process ultimately results in a choice founded on the individual’s goal of maximizing their “expected utility.”25Id.25

An economic principle closely related to the decision-making process above is the concept of information asymmetry. This phenomenon rests on the idea that the market “and other systems involving human decisions (like elections)” operate as decision-making systems that require information to function effectively.26Tim Wu, An Introduction to the Law & Economics of Information at 10, Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper 482 (2016).26 Hence, when “information is scarce, or if distributed asymmetrically, systemic failure can be expected.”27Id.27 Tim Wu asserts that information asymmetry pertains to the “distribution, as opposed to the creation of information.”28Id. at 3.28 For the purposes of this study, consider a counsel representing clients in court. The counsel needs to have all relevant information and details about the clients’ cases to represent them properly. Information asymmetry would arise in this scenario if the clients were to withhold information from their counsel, leading to an uneven or asymmetrical distribution of information between the parties. This is why Joel Waldfogel, in his analysis of asymmetric information theory applied to litigation, stated that “parties proceed to trial only when they expect to win,” meaning they are sufficiently informed to assess their “actual likelihood of prevailing at trial.”29Joel Waldfogel, Reconciling asymmetric information and divergent expectations theories of litigation, 41(2) J.L. & ECON. 451, 451, 455 (1998).29

A. Investor-State Dispute Settlement as a Result of a Market Failure

One practical way to understand the significance of the concept of market failure in the economic analysis of law is through its role in creating legal systems. The ISDS system provides a clear example of this. As previously mentioned, market failure occurs when the allocation of resources is inefficient, meaning it is not “Pareto-optimal.”31Ledyard, supra note 6, at 1.31 Alan Randall states that when markets fail, they often turn to the government for “ameliorative measures,” such as laws, taxes, and regulations.32Alan Randall, The Problem of Market Failure, 23(1) NAT. RES. J. 131, 131 (1983).32

What is the reasoning behind claiming that ISDS is the result of a market failure? To address this issue, it is essential to comprehend the nature of this dispute resolution mechanism. ISDS is the result of using “international law as a tool of investor protection.”33Robert Howse, International Investment Law and Arbitration: A Conceptual Framework, in INTERNATIONAL LAW AND LITIGATION: A LOOK INTO PROCEDURE 363, 370 (Hélène Ruiz Fabri ed., 2019).33 The origin of this mechanism dates back to the 19th and 20th centuries when capital exporters aimed to ensure their investors received “[a] minimum standard of treatment . . ., including access to justice and protection against expropriation.”34Id.34 According to Rudolf Dolzer and Christoph Schreuer, before “the Communist Revolution in Russia in 1917, neither State practice nor the commentators of international law had reason to pay special attention to rules protecting foreign investment.”35RUDOLF DOLZER, URSULA KRIEBAUM, & CHRISTOPH SCHREUER, PRINCIPLES OF INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT LAW 3 (3rd ed. 2022).35 As a result, the prevailing approach was the use of force known as “gunboat diplomacy.”36Howse, supra note 33, at 371; DOLZER, KRIEBAUM, & SCHREUER, supra note 35, at 3. 36 An illustration of this was the 1902-armed intervention by the British, German, and Italian navies against Venezuela, which was aimed at protecting the interests of their citizens who held claims related to state bonds that the Venezuelan government had refused to pay.37DOLZER, KRIEBAUM, & SCHREUER, supra note 35, at 3.37

The process of decolonization after World War II brought about a shift in the status quo above, as newly independent countries sought complete authority and control over their natural resources.38Howse, supra note 33, at 371; DOLZER, KRIEBAUM, & SCHREUER, supra note 35, at 371.38 This shift represented a significant investment risk for foreign investors because of the lack of clarity regarding the “customary law governing foreign investment” in these newly independent, capital-importing countries.39DOLZER, KRIEBAUM, & SCHREUER, supra note 35, at 6.39 In response, capital-exporting countries took various actions. For example, the United States implemented its friendship, navigation, and commerce treaties, which, according to Wolfgang Alschner, focused on protecting “investment abroad” after 1945.40Wolfgang Alschner, Americanization of the BIT Universe: The Influence of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation (FCN) Treaties on Modern Investment Treaty Law, 5(2) GOETTINGEN J. INT’L L. 455, 462 (2013).40 The author argues that these treaties were more “than a historical precursor to international investment agreements,” as they “continue to influence and inspire modern investment treaty design.”41Id. at 456.41

The historical background above illuminates the market failure that led to the development of ISDS, which aims to protect investments of investors from capital-exporting countries into newly independent countries during the 19th and 20th centuries. In other words, ISDS sought to address a market failure in the protection of foreign investment against “political risk to the investor.”42Howse, supra note 33, at 372.42 This includes safeguarding against expropriation without compensation, discrimination, and failure to provide due process.43DOLZER, KRIEBAUM, & SCHREUER, supra note 35, at 8-10.43 From an economic standpoint, political risk impedes market efficiency and discourages foreign investment.44Nabamita Dutta & Sanjukta Roy, Foreign Direct Investment, Financial Development and Political Risks, 44(2) J. DEVELOPING AREAS 303, 322 (2011).44 ISDS, in this context, was created as a tool to address these issues and facilitate foreign investment inflows.45Id. at 306.45

B. Third-Party Funding, Another Result of a Market Failure

Kehinde Olaoye and Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah state that the ISDS system is currently experiencing the fifth stage of its history, referred to as the “Backlash.”47Kehinde Folake Olaoye & Muthucumaraswamy Sornarajah, Domestic investment laws, international economic law, and Economic Development, 22(1) WORLD TRADE REV. 109, 119 (2023).47 Presently, there are several critiques of the system, one of which is the high “costs and duration” of the arbitration proceedings.48See Secretariat of U.N. Comm’n on Int’l Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Working Grp. III, Possible reform of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS) — cost and duration ¶¶ 4-12, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.153 (Aug. 31, 2018), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v18/057/51/pdf/v1805751.pdf [hereinafter UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Cost and duration].48 The UNCITRAL Working Group III has acknowledged that investment arbitration is an expensive proposal, particularly affecting small and medium-sized investor claimants. It identified that the “[i]ncreasing cost of ISDS proceedings may limit the access of such enterprises to ISDS mechanisms or deter their use, thus depriving them of the protection provided to them under investment treaties.”49Id. ¶ 9 (emphasis added).49

The statement by the UNCITRAL Working Group III above is pivotal to introducing the concept of third-party funding. When investors covered by an arbitration agreement between their home state and the host state cannot pursue a claim against the host state due to insufficient resources, they experience a market failure in the form of restricted access to justice.

Jonathan Molot developed the concept of market failure in accessing justice. The author poses the question of why a claimant would accept an unfavorable settlement that represents “less than the expected value of the suit?”50Jonathan T. Molot, Litigation Finance: A Market Solution to a Procedural Problem, 99(1) GEO. L.J. 65, 83 (2010).50 Molot identifies two main issues: “litigation expenses and risk aversion.”51Id.51 Litigation expenses refer to the costs involved in pursuing a legal claim before a tribunal, whereas risk aversion is the tendency for individuals to avoid an outcome worse than expected. Early settlement can be beneficial when both parties share the same concern regarding potential outcomes. However, a problem arises when “the parties have different risk tolerances, this imbalance in risk preferences may lead to an imbalance in bargaining power and to a settlement that departs dramatically from the mean expected jury award,”52Id. at 84.52 as Molot describes.

In the scenario Molot presented, there are two parties involved: (i) a “one time, risk adverse participant” and (ii) a “repeat-player” who is willing to bear the consequences of an unfavorable ruling.53Id. at 65.53 Molot’s mathematical model can be used to examine an investment dispute scenario.54Id. at 86.54 In his example, a medium-sized investor is not in a favorable position to allocate significant resources towards a claim against a state that may have breached the investor’s rights under the respective investment agreement.

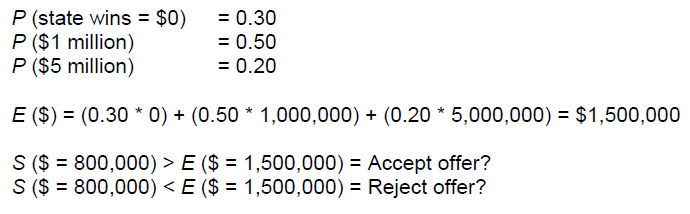

The potential arbitration outcomes (P) are as follows: (i) a 30% chance that if the state wins the case, the claimant will receive no compensation (with a value of 0); (ii) a 50% chance of the state losing the case and being ordered to pay $1 million in compensation; and (iii) a 20% chance of the state losing the case and being ordered to pay $5 million in compensation. The expected average compensation (E) for each outcome is calculated by multiplying the probability by the outcome, resulting in $1,500,000.55See id. at 86 n. 64 (applying the expected value).55 In this scenario, the investor may feel compelled to accept a settlement offer (S) of $800,000, which is less than the average expected compensation, to avoid the risk of losing the case and receiving no compensation. This would benefit the state because it could save $700,000 by paying only $800,000 instead of the full $1,500,000. A basic mathematical model can represent the above situation as follows:

The above illustrates the consequences of a market failure in accessing justice.56Id. at 88. 56 If the investor had been able to resort to arbitration, they could have potentially recovered $1,500,000. Moreover, access to arbitration would have bolstered the investor’s bargaining position when negotiating with the state, providing a stronger stance to reject the settlement offer. As Molot states, such a scenario could be possible if there is a “repeat-player, risk-neutral entity on the [claimant’s] side,” as this could, for instance, “promote more accurate deterrence.”57Id. at 89.57 Molot suggests that this “risk-neutral entity” typically takes the form of a “third-party financier.”58Id. at 89, 100.58

The emergence of third-party funding is a direct result of the market failure where a claimant is denied access to justice or deterred from seeking legal recourse. This failure occurs when claimants (i) lack resources, (ii) have inadequate understanding of the litigation process and “procedural risks,” (iii) have uncertainty and risk aversion, or (iv) have “difficulty” determining the value of the claim.59GIAN MARCO SOLAS, THIRD PARTY FUNDING: LAW, ECONOMICS AND POLICY 174 (2019).59

In the context of ISDS, the UNCITRAL Working Group III has defined third party funding as follows:

[A]n agreement by an entity (the ‘third-party funder’) that is not a party to a dispute to provide funds or other material support to a disputing party (usually the claimant or a law firm representing the claimant), in return for a remuneration, which is dependent on the outcome of the dispute. The remuneration can take any form, though more common forms include a multiple of the funding, a percentage of the proceeds, a fixed amount, or a combination of the above.60Secretariat of UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible reform of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS): Third-party funding ¶ 5, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.157 (Jan. 24, 2019), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v19/004/07/pdf/v1900407.pdf [hereinafter UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding].60

The ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force on Third-Party Funding in International Arbitration identified the “key participants in the dispute funding process.”61Int’l Council for Comm. Arb. (ICCA), Report of the ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force on Third-Party Funding in International Arbitration: The ICCA Reports No. 4 at 20 (2018), https://cdn.arbitration-icca.org/s3fs-public/document/media_document/Third-Party-Funding-Report%20.pdf [hereinafter ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report].61 The investor claimant, the first player, may be either solvent or insolvent. However, for purposes of this explanation, assume the claimant is “a party that has invested all of its resources into a failed project and funding provides this investor with the only mechanism by which the investor can seek redress from the parties that caused its losses.”62Id. at 20.62

The second player are law firms. The ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force noted that the “role played by law firms in the third-party funding market is multi-faceted.”63Id. at 21.63 In some cases, law firms may already have a connection to the funders. Their responsibility may include “preparing a case for presentation to funders, understanding that it will only be able to recoup that time investment if funding is successfully obtained.”64Id. at 21-22.64

The third player in the funding process is the broker. Brokers serve as intermediaries and their role, as the ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force specified, “is to advise on potential financing options, access a broader range of funders, and manage the process,” stating that “brokers are regarded as playing an increasingly prominent role in the process of sourcing and structuring dispute finance arrangements.”65Id. at 22–23.65

The final key player in the funding relationship is the funder, whose role has already been described above. The funding process relies on a self-sustaining system where each individual involved functions as an organ of a body, performing their respective task to ensure the mechanism operates smoothly.

Third-Party Funding, a Problematic Issue in ISDS

As part of its reform agenda, the UNCITRAL Working Group III has identified third-party funding as a critical issue in ISDS, given how this practice has become increasingly prevalent.1UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Report of Working Group III (Investor-State Dispute Settlement Reform) on the work of its thirty-fifth session (New York, 23–27 April 2018) ¶ 89, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/935 (May 14, 2018), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/v18/029/59/pdf/v1802959.pdf.1 It has also been recognized that this is a complicated area where various forms of financing are present.2UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding, supra note 59, ¶ 9.2 Further, there is widespread agreement that third-party funding is an unregulated matter within international arbitration. The ongoing debate revolves around the extent to which this mechanism should be “permitted or regulated.”3Id. ¶ 12.3

According to the UNCITRAL Working Group III, third-party funding poses serious challenges to the legitimacy of the ISDS system,4Id. ¶ 16.4 with two particular concerns capturing considerable attention.5Secretariat of UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible reform of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS): Security for costs and frivolous claims ¶ 3, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.192 (Jan. 16, 2020), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v20/003/85/pdf/v2000385.pdf [hereinafter UNICTRAL Working Grp. III, Security for costs and frivolous claims].5 These issues revolve around the potential rise in “speculative, marginal and/or frivolous claims” flooding the ISDS system as well as the topic of “security for costs.”6UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding, supra note 59, ¶¶ 27, 34.6 This section delves into a law and economics perspective to shed light on these issues, aiming to show that they are real and pressing challenges that erode the legitimacy of the ISDS system.

A. Does Third-Party Funding Promote Frivolous Claims?

The concept of frivolous claims is intertwined with the notion of risk. As the case becomes riskier, the expected outcome becomes significantly more uncertain.8Molot, supra note 49, at 84-85.8 According to Tsai-fang Chen, frivolous claims are defined as claims lacking “legal merit” and therefore having “no real possibility of prevailing.”9Tsai-fang Chen, Deterring Frivolous Challenges in Investor-State Dispute Settlement, 8(1) CONTEMPORARY ASIA ARB. J. 61, 63 (2015).9 Frivolous claims filed in the ISDS system have various negative impacts, including increasing the overall number of cases10Secretariat of UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible reform of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS): Third-party funding – Possible solution ¶ 5, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.172 (Aug. 2, 2019), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v19/083/90/pdf/v1908390.pdf [hereinafter UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible solution].10 and creating a burden for respondent states that must invest time and resources to defend themselves in new arbitration proceedings.11Chen, supra note 72, at 64.11

To fully comprehend the impact of such claims, it is essential to consider the direct costs of arbitral proceedings, which include: “expenses of the arbitrators; costs associated with the administration of proceedings, including the fees of arbitral institutions; fees of appointing authorities; the costs of expert advice and other assistance required by the tribunal; travel and expenses of witnesses; and attorneys’ fees.”12Id. at 70.12 The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) provided an example of the costs that a state may incur when defending itself in ISDS proceedings. Notably, the Czech Republic is reported to have spent around $10 million in costs defending the CME Czech Republic B.V. v. Czech Republic13CME Czech Republic B.V. v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL, Final Award (Mar. 14, 2003). 13 and Lauder v. Czech Republic14Lauder v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL, Final Award (Sept. 3, 2001). 14 cases.15United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Investor-State Disputes Arising from Investment Treaties: A Review at 10 (2005), https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/iteiit20054_en.pdf. 15 Furthermore, Daniel Chen’s comprehensive study on litigation funding revealed that the funded cases he analyzed “appear riskier over time as indicated by a greater spread in the profit and loss in case outcomes.”16Daniel L. Chen, Can markets stimulate rights? On the alienability of legal claims, 46 Rand J. Econ. 23, 38 (2015).16

From a law and economics perspective, the assertion that third-party funding encourages frivolous claims seems non-sensical. According to Pacces and Visscher, law and economics is defined “as the application of the rational choice approach to law.”17Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [2].17 As previously stated, the rational-choice theory posits that individuals are rational decision-makers seeking to maximize their expected utility. Pacces and Visscher emphasize that this principle is “outcome-oriented,” meaning that “in order to reach a goal, an actor employs the available means.”18Id.18

Considering the above, it would be illogical for a funder to invest in a claim with the intention of incurring losses. As Michael Abramowicz highlights, funders only invest in claims “when they expect to profit from doing so.”19SOLAS, supra note 58, at 186 (“The main incentive of third-party funders is, needless to say, making profit. The more profit they make, the more they can fund cases and grow as a business. Being rational profit maximisers, they will be willing to fund claims when their expected profits E(π) F are positive, which in theory would mean that funders would only fund meritorious cases.”); see also Michael Abramowicz, On the Alienability of Legal Claims, 114(4) YALE L.J. 697, 744 (2005) (“[t]hird party likely to purchase claims only when they expect to profit from doing do”).19 What then motivates a funder to invest in what may be perceived as a frivolous claim? Two main explanations emerge. First, the availability of new risk-mitigating mechanisms, such as after-the-event (“ATE”) insurance, provide funders with avenues to minimize risks. Second, information asymmetry may also be contributing to the bringing of unmeritorious claims.

1. ATE insurance

ATE insurance, also known as litigation or arbitration insurance, is purchased after a legal dispute “has arisen and covers the risk that the insured party will be unsuccessful in the litigation/arbitration.”21ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 34. 21 The ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force has identified this insurance as a complementary tool to third-party funding, suggesting that an investor claimant could utilize both simultaneously.22Id. at 54-55.22

Understanding how these mechanisms complement each other is crucial. The third-party funder is responsible for funding the claim, while the insurer’s role is to “to meet any adverse costs award.”23Id. at 160.23 To illustrate this scenario with a mathematical model, it is necessary to consider the specificities of cost allocation in ISDS.

In international arbitration, it is widely recognized that “tribunals generally have broad discretion when deciding on cost allocation.”24Steven Finzio & Cem KalelioÄŸlu, Allocation of Costs ¶ 11, JUS MUNDI (2020), https://jusmundi.com/en/document/publication/en-allocation-of-costs; see also UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Cost and duration, supra note 47, ¶¶ 29-31.24 There are two primary methods for allocating costs in ISDS: the “loser pays” approach (also known as the English Rule) where “the losing party compensates the prevailing party for the costs it has incurred”25Finzio & KalelioÄŸlu, supra note 86, ¶ 11.25 and the American rule where “each party bears its own legal costs and its proportional share of the arbitration costs.”26Id.26

For the mathematical models below, the reader should bear in mind that there is limited information on third-party funding practices in international arbitration due to the confidentiality of the financing contracts.27ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 29.27 In a recent book on third-party funding in investment arbitration, Can Eken presents empirical research based on interviews with funders addressing issues such as the decision-making process for funding cases.28CAN EKEN, THIRD-PARTY FUNDING IN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION A NEW PLAYER IN THE SYSTEM (2024).28 This analysis will incorporate Eken’s findings, providing direct insights from funders and enhance the credibility of the mathematical models developed below.

Eken’s research revealed that funders generally support cases with a minimum value of USD 10 million.29Id. at 118.29 The study also found that most funders adhere to a guideline of maintaining a 1/10 ratio between the requested funding amount and the claim’s actual value.30Id. at 114-15.30 Regarding funder fees, Eken found that they are typically determined in one of two ways.31Id. at 117-18.31 The first method involves the funder taking a percentage of the awarded amount and the second involves taking a multiple of the funder’s investment. Some funders have published their fees, which ranged from 20% to 30% of the awarded amount.32Risk-free litigation financing, ALLIANZ (Aug. 17, 2007), https://www.allianz.com/en/press/news/business/insurance/news-2007-08-17.html.32 More recently, the ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force stated that this average can be as high as 40%.33ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 25-26.33

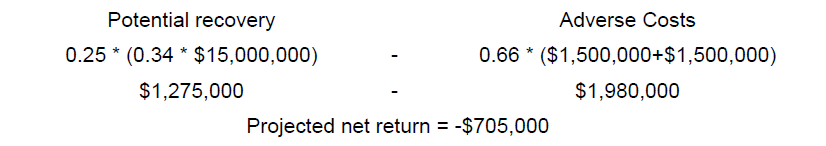

The mathematical models below are developed under the loser pays rule. It is important to note that these mathematical models are a simplified version of the ones developed by Solas.34SOLAS, supra note 58, at 186-89.34 In this hypothetical investment arbitration scenario, a medium sized investor seeks to bring a claim against a state with a total claim value of $15,000,000. Under the loser pays rule, the losing party would cover the representation and arbitration costs incurred by both parties, amounting to $1,500,000/party. The investor and the third-party funder have agreed on a compensation percentage of 25% of the recovery. Further, the probability of success in this case is 1/3 (34%) due to the frivolous nature of the claim. This scenario is represented as follows:

This scenario highlights that the third-party funder’s projected profit from funding this claim amounts to $1,275,000, while the estimated potential adverse costs add up to $1,980,000. Given that the potential adverse costs exceed the expected benefit, the funder would face a negative bottom line, likely leading to the decision not to finance this claim.

However, introducing ATE insurance alters the scenario by mitigating a potential adverse costs award by the tribunal.35SOLAS, supra note 58, at 83.35 Building on Solas’ model,36Id. at 186-89.36 assume the ATE insurance premium is $150,000. As a result, there is no need to include the opposing party’s legal expenses in the equation, as the funded investor claimant would be solely responsible for paying its legal expenses and the ATE insurance premium. The value displayed below as $1,650,000 reflects these concepts. Including the ATE insurance alters the outcome of the previous example:

Incorporating the ATE insurance premium would lead to potential adverse costs of $1,089,000 for the funded investor claimant. Subtracting this amount from the expected potential recovery for the third-party funder of $1,275,000 results in a favorable outcome of $186,000. This example demonstrates how ATE insurance can impact the predicted outcomes for a third-party funder, even in cases involving frivolous claims.

2. Information asymmetry

As stated above, in law and economics, information asymmetry occurs when information is distributed unevenly. In the context of third-party funding in ISDS, the ICCA Queen-Mary Task Force acknowledged that “[s]ecuring funding necessarily requires the sharing of confidential, privileged and, on occasion, highly sensitive information with prospective funders.”38ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 29.38

The information held by the prospective claimant is pivotal because it serves as the basis for potential funders during their due diligence processes.39Id. at 72.39 In conducting these assessments, funders can seek assistance from “external counsel, and potentially damages or technical experts.”40Id. at 25.40 The ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force highlighted that:

To assess risk . . . commercial third-party funders generally create a risk-assessment model or matrix that takes into account the percentage likelihood of different outcomes in light of specific factors. These factors include, among others, the jurisdiction of the claim, strength of the claimant’s legal arguments, strength of facts supporting the arguments, extent of loss flowing directly from the respondent’s conduct, a claimant’s motivation, commitment and honesty, the experience of the claimant’s legal team, the respondent’s ability/likelihood to pay, reasonable duration to obtain an award, and costs of bringing the claim.41Id. at 72.41

Information asymmetry may exist in the context of third-party funding where “claimholders, in order to attract capital to fund a case, would highlight only the positive aspects of their cases (thus engendering an issue of adverse selection and moral hazard).”42SOLAS, supra note 58, at 242.42 Abramowicz’s work on adverse selection in the market for claims highlighted, for instance, that a claimant might withhold information to a funder about a potential witness whose testimony could harm their case.43Abramowicz, supra note 82, at 743-45.43 Information asymmetries can also arise during the arbitration process. In such instances, inadequate communication results in “information asymmetries between the attorney and the funder and lowers the funder’s ability to supervise the attorney’s work.”44Maya Steinitz, Whose Claim Is This Anyway? Third Party Litigation Funding, 95(4) MINN. L. REV. 1268, 1323 n. 195, 1324 (2011).44

While the ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force reported that “[l]ending funders report an average review-acceptance rate of 10-1,”45ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 17, 71.45 acknowledging the challenges posed by information asymmetries is crucial in the funder’s due diligence process concerning the claimholder’s case, as the complexity of an ISDS case increases the likelihood of information asymmetry occurring.46Eken, supra note 90, at 146.46 Consequently, a claim that initially appears robust may turn out to be frivolous during arbitration if the claimant fails to disclose vital facts, documents, or witnesses to the funder before the arbitration commences.

The two analyses above illustrate that existing mechanisms, such as ATE insurance, and information asymmetries between the claimant and funder may contribute to an increase in frivolous claims within the ISDS system. This, in turn, can lead to a market failure. As mentioned earlier, market failure occurs when resources are allocated inefficiently within markets. In this context, funder resources that could have been allocated to the meritorious cases of impecunious claimants may instead be directed toward funding frivolous claims. This supports the need for new regulation of third-party funding, as described below. However, before addressing a proposal for regulation, a second issue is examined below: the impact of third-party funding on obtaining security for costs in ISDS.

B. Does Third-Party Funding Justify Requesting an Order for Security for Costs?

1. Securing costs, but of what and for what?

The issue of security for costs is a significant concern for states facing funded claims with no assurance of recovering the resources expended for legal defense. In ISDS, the concept of security for costs involves a measure at the tribunal’s discretion aiming to address “the risk that a party to a dispute does not comply with an adverse cost award . . . oblig[ing] the party to provide security to cover the estimated cost that the other party will incur in defending itself against the claim.”49UNICTRAL Working Grp. III, Security for costs and frivolous claims, supra note 69, ¶ 5.49 When considering whether to grant a request for security for costs, the tribunal typically applies the “two-part test.”50Xuan Shao, Disrupt the gambler’s Nirvana: Security for costs in investment arbitration supported by third-party funding, 12(3) J. INT’L DISP. SETTLEMENT 427, 434 (2021).50 This test involves determining whether the presence of third-party funding “makes such an order necessary and urgent” and whether it may hinder the “claimant’s ability to pursue its claim.”51Id. at 440.51

It is crucial to distinguish between two scenarios regarding this issue. As mentioned earlier, third-party funding serves as a tool to address the inability to access justice for impecunious claimants. However, it is acknowledged that this mechanism may also be utilized by solvent claimants.52See SOLAS, supra note 58, at 175; UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding, supra note 59, ¶ 31; Shao, supra note 109, at 439.52 In such instances, the primary purpose of this mechanism is forfeited, as it is no longer being used to facilitate access to justice but rather as a form of “risk management.”53UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding, supra note 59, ¶ 31.53 This scenario can be explained by two concepts: risk mitigation and corporate finance. A solvent party might seek funding when the outcome of a potential claim is uncertain to avoid risk.54SOLAS, supra note 58, at 175.54 In terms of corporate finance, a party may seek funding for a claim, for instance, to allocate its resources in a different project that is more closely related to its core business.55Id. at 178.55

It is important to note that security for costs can pose a problem in ISDS if the party against whom the order is directed is an insolvent party. This issue has been treated differently by various ISDS arbitral tribunals. In García Armas v. Venezuela,56García Armas v. Venezuela, PCA Case No. 2016-08, Procedural Order No. 9 (June 20, 2018). 56 the tribunal highlighted that the claimants’ claims were entirely funded by a third-party funder.57Id. ¶ 242. 57 The funding agreement did not cover an adverse costs award, thus making the claimants’ solvency a crucial factor in determining the order of security for costs.58Id.58 The tribunal identified two factors: the funding agreement’s existence and its inability to cover an adverse costs award. This meant that there was a possibility that the claimants were insolvent, which, in turn, increased the likelihood that the respondent would not be compensated for its costs if the claims failed.59Id. ¶ 245.59 The tribunal stated that the burden of proof rested with the claimants to demonstrate their solvency, as these circumstances were only known to them. As the claimants failed to demonstrate their financial ability to cover any potential costs awarded against them, the tribunal granted Venezuela security for costs.60Id. ¶¶ 250-51.60

The tribunal’s decision in García Armas could undermine third-party funding’s intended purpose of ensuring access to justice. By imposing additional financial burdens on already cash-strapped claimants, the decision risks deterring those who, without third-party funding, would be unable to pursue an ISDS claim. Interestingly, the Herzig v. Turkmenistan61Herzig v. Turkmenistan, ICSID Case No. ARB/18/35, Decision on Security for Costs (Jan. 27, 2020).61 tribunal supported this position. The tribunal considered the same factors mentioned in García Armas,62Id. ¶ 57.62 namely, that the claimant relied on third-party funding and the funder was “not liable under the funding contract for an ultimate award of costs in Turkmenistan’s favor.”63Id. 63 Therefore, Turkmenistan’s request for security for costs was granted.64Id. ¶ 84.64 However, six months after this order, the tribunal reversed its decision based on the claimant’s request for reconsideration.65See Shao, supra note 109, at 431-32 (citing Herzig v. Turkmenistan, ICSID Case No. ARB/18/35, Procedural Order No. 5 (June 9, 2020) (unpublished)).65 In this “June decision,”66Id.66 the tribunal stepped back and recognized that preventing the claimant from defending its claims would effectively deny access to justice.67Id.; see also Christina L. Beharry, Herzig v Turkmenistan - Requests for security for costs in ICSID arbitrations involving third-party funded insolvent claimants, 36(1) ICSID REV. 14, 22 (2021).67 However, one of the arbitrators dissented, arguing that the claimant’s right to access justice does not override the principle of equality of arms, which includes the prevailing party’s entitlement to recover arbitration costs if awarded a favorable costs decision.68Shao, supra note 109, at 432 (citing Herzig, Procedural Order No. 5).68

The scenario above demonstrates the intricacy of the security for costs issue when an insolvent claimant is backed by a third-party funder who is not obliged to cover an adverse costs award. This complexity arises from the tension between the claimant’s need for financial support to pursue the claim and the respondent state’s interest in ensuring the ability to recover its arbitration costs if it prevails. The intricacy lies in balancing these competing concerns of ensuring access to justice for cash-strapped claimants while safeguarding the respondent’s right to recover costs in the event of a favorable outcome.

2. A law and economics analysis

The aforementioned issues can be better comprehended or mitigated through the application of the economic principles of efficiency and deterrence.

First, as mentioned before, efficiency in law and economics aims to achieve the most “optimal allocation” of resources.70Parisi, supra note 1, at 267.70 Jolls et al. assert that the “third fundamental principle of conventional law and economics is that ‘resources tend to gravitate toward their most valuable uses.’”71Jolls et al., supra note 21, at 1483 (citing RICHARD A. POSNER, ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF LAW 11 (5th ed. 1998)). 71 However, in the context of security for costs, there is inefficiency in how tribunals establish the burden of proof for claimants to demonstrate their financial capacity.72Shao, supra note 109, at 435.72 For example, in Victor Pey Casado v. Chile,73Pey Casado v. Chile, ICSID Case No. ARB/98/2, Decision on Provisional Measures (Sept. 25, 2001).73 South American Silver v. Bolivia,74South American Silver Ltd. v. Bolivia, PCA Case No. 2013-15, Procedural Order No. 10 (Jan. 11, 2016).74 and Eskosol v. Italy,75Eskosol S.p.A. in liquidazione v. Italy, ICSID Case No. ARB/15/50, Procedural Order No. 3 (June 12, 2017).75 the tribunals determined that the respondent states bore the burden of proving that the claimants lacked the resources to cover potential adverse costs awards.76See Pey Casado ¶ 89; South American Silver ¶ 74; Eskosol ¶ 37.76 Due to the challenges faced by the states in gathering the necessary information in these cases, the tribunals rejected all their requests for security for costs.77See Pey Casado ¶ 89; South American Silver ¶¶ 64-67; Eskosol ¶¶ 37-39.77

It is evident that claimants have easier access to their databases and are thus better placed to obtain information proving their financial capacity. For instance, the García Armas tribunal placed the burden of proof on the claimants when it considered that obtaining all relevant information on the claimant’s financial capacity was beyond the reasonable scope of information within the respondent’s reach.78Garcia Armas ¶ 248; see also Shao, supra note 109, at 440-41.78 Therefore, a law and economics analysis would conclude that the most efficient solution to this issue is to place the burden of proof on funded claimants to demonstrate their financial capacity. This approach would save time and resources for all parties involved in the arbitration as well as the tribunal.79Shao, supra note 109, at 441.79

Second, the “deterrence effect”80Marco de Morpurgo, A Comparative Legal and Economic Approach to Third-party Litigation Funding, 19 CARDOZO J. INT’L & COMP. L. 343, 382 (2011). 80 is another economic principle at play in the scenario of security for costs. According to Macro de Morpurgo, “[o]ptimal deterrence requires potential insurers to be aware of the fact that they will bear full costs of the harm they produce.”81Id. 81 Due to the absence of established standards regarding the burden of proof for requesting security for costs as a provisional measure in ISDS, insolvent parties with higher-risk claims may not feel deterred from resorting to arbitration. Thus, from an economic standpoint, a presumption in favor of security for costs could deter speculative investors and funders.

Nonetheless, a law and economics perspective must grapple with the central challenge in this context: the costs-benefits analysis between access to justice and equality. Initially, neither option seems entirely equitable. Should ISDS align with an approach akin to García Armas that leads to a situation where claimants with bona fide claims but limited financial resources might have difficulties complying with security for costs orders?82See Shao, supra note 109, at 443; see also Herzig v. Turkmenistan, ICSID Case No. ARB/18/35, Decision on Security for Costs, ¶ 65 (Jan. 27, 2020) (“in the demonstratable event that Dr Herzig [the claimant] faces insurmountable obstacles in obtaining the bank guarantee ordered . . . [the tribunal may] reconsider its order for security for costs in view of the various considerations . . . including the need to ensure a party’s due access to an international tribunal”). 82 On the other hand, why should states invest substantially in their defense without assurance of recouping costs in the event of a successful defense? Notably, the dissenting arbitrator in Herzig strongly criticized the June decision that overturned the earlier security for costs order:

The proceedings have been engaged solely because a third-party funder . . . decided to invest in them, but on the condition that it not be exposed to the risk of paying any part of the other side’s costs in the event that its gamble – for that is what its investment amounts to – does not pay off. [The funder] hopes to obtain all the advantages of success, without bearing the burden of all the disadvantages of failure. In this way, the decision of the majority may be seen as giving a green light to an approach that maximizes the rate of return of a third-party funder at the expense of the legitimate interests – including the principle of equality of arms – of the respondent. Access to justice thereby risks becoming access to injustice.83Shao, supra note 109, at 444.83

The arbitrator’s sense of helplessness is apparent in his dissent as he emphasizes the tribunal’s current lack of effective means to ensure that a third-party funder will not “hide behind a claimant’s right to pursue its claim,” enabling it to “reap profits without bearing the corresponding risk.”84Id. at 443-44. 84 As Shao stated, “the root cause of the problem is that three parties are involved and interested in the arbitral proceedings, whereas only two of them are subject to the tribunal’s jurisdiction.”85Id. at 444.85

C. Preliminary Conclusion

There are intrinsic problems in the ISDS system arising from third-party funding, particularly in relation to the concerns about frivolous claims and security for costs orders. While risk mitigation mechanisms like ATE insurance are now commonly used by funders and claimants,87See Eken, supra note 90, at 126 (“From my interviews, this study can conclude that insurance, especially ATE insurance and TPF are definitely very close, and sometimes ATE insurance is included in the TPF agreements.”).87 states often face the dilemma of not having a guarantee to recover arbitration costs when defending against a funded claim.88See UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible solution, supra note 73, ¶¶ 34-38.88 These are real and structural issues, and the lack of regulation of third-party funding in ISDS makes it impossible to effectively address these concerns.

The absence of such regulation allows third-party funders to potentially exploit the system by financing claims without bearing the financial responsibility for adverse cost awards. This not only deviates from the original purpose of third-party funding—of facilitating access to justice—but also raises fundamental concerns about the fairness and integrity of the arbitration process.

Regulation, Widely Discussed, But Difficult to Enforce

Considerable debate surrounds the regulation of third-party funding in ISDS.1See id. ¶ 10; Frank Joseph Garcia, Third-Party Funding as Exploitation of the Investment Treaty System, 59(8) B.C. L. REV. 2911, 2928 (2018); Rachel Denae Thrasher, Expansive Disclosure: Regulating Third-Party Funding for Future Analysis and Reform, 59(8) B.C. L. REV. 2935, 2937 (2018); SOLAS, supra note 58, at 290.1 While numerous proposals have been suggested, only two viable options exist for a meaningful change: either to regulate third-party funding or prohibit it.2UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible solution, supra note 73, ¶¶ 15-20.2

A. Prohibition of Third-Party Funding?

This approach finds support from the governments of South Africa and Morocco within the UNCITRAL Working Group III.4Id. ¶ 15 n. 17.4 The discussions within the Working Group III suggest that if this option is adopted, alternative funding mechanisms like “legal aid” would need to be established.5Id. ¶¶ 17-19.5 However, prohibition is an impractical solution. As illustrated in the analysis of security for costs above, third-party funding plays a crucial role in enabling cash-strapped claimants with valid cases to access justice. Another challenge with prohibition lies in its enforcement, with critics like Frank Garcia arguing that third-party funding “should be barred from all ISDS cases until the system is fundamentally reformed both substantively and procedurally.”6Garcia, supra note 146, at 2929.6 Banning the funding mechanism in ISDS could theoretically occur by incorporating provisions in investment agreements.

However, this option is not practical from a logistical standpoint. Even if the states currently engaged in the UNCITRAL Working Group III discussions were to consent to incorporating provisions in their investment instruments prohibiting third-party funding, each state would be required to negotiate amendments to its existing agreements on an individual basis. UNCTAD reports that, as of now, there are 2,217 BITs in force and 370 treaties with investment provisions, underscoring the enormity of the task this option would entail.7International Investment Agreement Navigator, UNCTAD INVESTMENT POLICY HUB, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements.7

B. Regulating Third-Party Funding through an Opt-in Multilateral Mechanism

Considerable attention has been devoted to identifying the key aspects of third-party funding that require regulation. However, limited consideration has been given to how to effectively achieve such regulation. Therefore, this study, which has already exposed key problems regarding this mechanism, aims to focus on the most effective and practical way to regulate third-party funding. In this regard, an opt-in multilateral mechanism may be a viable, effective, and legally sound alternative under international law.

1. Promising examples of multilateralization

Multilateral instruments are not a novel concept in international law. Recent examples of such agreements include the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS Convention”)10Org. for Econ. Co-Operation and Dev. (OECD), Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent BEPS (2016), https://www.oecd.org/tax/treaties/multilateral-convention-to-implement-tax-treaty-related-measures-to-prevent-beps.htm [hereinafter BEPS Convention].10 and the United Nations Convention on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor–State Arbitration (“Mauritius Convention”).11U.N. CONVENTION ON TRANSPARENCY IN TREATY-BASED INVESTOR-STATE ARBITRATION, G.A. Res. 69/116, U.N. Doc. A/69/496 (Dec. 10, 2014), https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/transparency-convention-e.pdf [hereinafter U.N. TRANSPARENCY CONVENTION].11

The primary advantage of an opt-in multilateral instrument is its potential to modify “treaty networks . . . through a single instrument.”12Natalie Bravo, The Mauritius Convention on Transparency and the Multilateral Tax Instrument: models for the modification of treaties?, 25(3) TRANSNAT’L CORPS. 85, 106 (2018).12 Moreover, it is more practical to use because these agreements address narrow subject matters. For instance, the BEPS Convention solely focuses on base erosion and profit-shifting matters, and the Mauritius Convention is limited to rules on transparency in ISDS proceedings. According to Natalie Bravo, “[b]y dealing with narrow subject matters, the treaty makers of these multilateral conventions avoided engaging in the negotiation of controversial treaty issues for which consensus may be more difficult to reach.”13Id. at 101.13

The methods employed by the above instruments to modify treaties vary. The BEPS Convention aims to enhance the current framework of agreements on avoiding double taxation and to prevent tax evasion by multinational companies.14BEPS Convention, supra note 152.14 These double taxation agreements must already be in force and both state parties must have adopted the BEPS Convention for these agreements to be covered. The BEPS Convention employs a “positive-listing approach,” meaning that “its parties must notify the tax treaties they are willing to modify.”15Bravo, supra note 154, at 92.15

The Mauritius Convention applies only when the investor’s home state and the respondent state are parties to the Convention without having made a reservation; or in cases where only the respondent state is a party to the Convention and the investor’s state has made a reservation, but the claimant nevertheless accepts its application.16U.N. TRANSPARENCY CONVENTION, supra note 153, arts. 1, 2.1-2.16 Unlike the BEPS Convention, the Mauritius Convention takes a “negative-listing approach,” implying that “[i]n their reservations, parties must identify IIAs by title and by the name of the contracting States, to exclude them from the scope of application of the Convention.”17Bravo, supra note 154, at 97.17

The second key innovation of these multilateral instruments is that, instead of modifying on a treaty-by-treaty basis, they have “adopted the approach establish[ed] in Article 30 of the Vienna Convention [on the Law of Treaties], which deals with successive treaties dealing with the same subject matter. Thus, these multilateral conventions coexist with the treaties they modify.”18Id. at 102 (citing Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, opened for signature May 23, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331).18 It is worth noting that “the provisions of the multilateral conventions in all cases prevail over the ones of the treaties they modify, by either replacing them, modifying their scope of application or supplementing them.”19Id. at 103.19

A last notable feature of these instruments is their flexibility. For instance, all the provisions of the BEPS Convention are subject to reservations.20Id. at 93.20 In the case of the Mauritius Convention, the instrument allows the parties not to apply the Convention if the process is conducted using arbitration rules other than the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules,21U.N. TRANSPARENCY CONVENTION, supra note 153, arts. 1, 3.1.b.21 such as those of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

Furthermore, it is worth noting that renowned ISDS scholars have highlighted the innovative and promising nature of these instruments. Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler and Michele Potesta acknowledged that the success of the Mauritius Convention lies in its capacity to “import” transparency rules into a fragmented treaty system through a “multilateral instrument” and “achieve[] this importation by sidestepping the need for amending the 3,000 existing [international investment agreements].”22Michele Potesta & Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler, Can the Mauritius Convention Serve as a Model for the Reform of Investor-State Arbitration in Connection with the Introduction of a Permanent Investment Tribunal or an Appeal Mechanism? – Analysis And Roadmap at 30, UNCITRAL (2016), https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/cids_research_paper_mauritius.pdf.22 Regarding the BEPS Convention, Alschner stated that such an instrument in the ISDS regime “could plug contractual gaps in outdated [international investment agreements] by incorporating state-of-the-art language on how to balance investment protection concerns with a host state’s regulatory interests, as well as how to reform ISDS and regulate hitherto unaddressed grey areas.”23Wolfgang Alschner, The OECD Multilateral Tax Instrument: A Model for Reforming the International Investment Regime?, 45(1) BROOK. J. INT’L L. 1, 56 (2019).23

2. A multilateral instrument on third-party funding

Adopting a multilateral instrument to regulate a narrowly defined area of the ISDS system is a viable solution. If accomplished, for instance, with rules on transparency, why could it not likewise be possible to address third-party funding issues? A counterargument to this statement could be that, unlike the Mauritius Convention, an instrument that regulates third-party funding would be addressing “controversial treaty issues,”25Bravo, supra note 154, at 101.25 making it difficult to reach a consensus between states.

This concern is valid to a certain extent. A multilateral instrument regulating third-party funding may possess a comparable degree of flexibility as with the BEPS Convention, i.e., that all its provisions can be subject to reservation. This would present harmonization challenges. However, there are some concerns on third-party funding that are widely accepted, such as disclosure of the funding relationship. Hence, not all provisions would be susceptible to a significant number of reservations.

(i) Law and economics efficiency analysis

The proposed multilateral instrument would integrate the flexibility features of the BEPS Convention, enabling contracting states that adopt the agreement to introduce reservations to provisions governing third-party funding. The efficiency of this crucial feature could be better understood through the principle of subsidiarity, which, according to Aurelian Portuese, is a “principle of economic efficiency.”26Aurelian Portuese, The Principle of Subsidiarity as a Principle of Economic Efficiency, 17(2) Colum. J. Eur. L. 231, 234-36 (2011). It is important to note that the subsidiarity principle, has been practically applied as one of the European Union’s governing principles. See id. at 233; see also Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union art. 5(3), 2012 O.J. C 326/13.26 For Portuese, subsidiarity dictates that decision-making should occur at the “most appropriate level of governance,” whether centralized or decentralized.27Portuese, supra note 167, at 232.27 Portuese further explains that “decentralization guarantees efficiency gains” by ensuring that decisions are made at the most immediate level where there is a diversity of preferences.28Id. at 235, 239.28 In other words, decentralization is the process through which subsidiarity is implemented.29Id. at 235-36.29 When there is a diversity of preferences among the subjects of regulation, decision-making should be left to them, as they are in immediate contact with the issues the regulation aims to address. From an economic efficiency standpoint, Portuese further contends that decentralization creates key efficiency gains.30Id. at 236.30

First, decentralization “produces a greater variety of regulations,” giving local authorities decision-making and planning powers and thus avoiding “information gathering costs.”31Id.31 For instance, when a central government is responsible for regulating an entire economy, these costs tend to increase. Portuese argues that this phenomenon is rooted in Hayek’s “knowledge problem,” wherein gathering crucial information “to police the economy and synthesizing this information on an ongoing basis requires both a high level of detail and a great effort on the part of the central planner.”32Id. (citing Friedrich A. Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society, 35 AM. ECON. REV. 519, 519 (1945)). 32 As a result, when decision-making is entrusted to local governments, “individuals and firms are able to choose the regulation that maximizes their utility.”33Id. at 236.33

Second, “[t]he choice of regulations serves to limit the administrative and bureaucratic costs of the Leviathan,” representing a central bureaucratic government that seeks to “regulate the economy to the detriment of consumers . . . and thus increase the prices attached to regulations while reducing overall economic efficiency.”34Id. at 237.34 Decentralization allows local governments to propose regulations that enhance the “competition [of] legal norms,” which “may bring about a sort of Darwinian evolution whereby the most efficient rules survive.”35Id.35

In the context of regulating third-party funding in ISDS, subsidiarity—as a principle of economic efficiency—suggests that states should have the autonomy to propose and adopt regulations that best align with their interests and legal contexts. If regulatory decisions were centralized and proposed through a treaty that does not allow reservations, especially on a sensitive issue like third-party funding,36Solas supra note 58, at 307 (discussing the regulation of third-party funding).36 it is unlikely that such a treaty would be broadly accepted within the international community. The ability for states to opt in and introduce reservations is essential for achieving both regulatory effectiveness and widespread adoption. The experience of the BEPS Convention supports this assertion. As Alschner stated:

[T]he [BEPS Convention] achieved a significant reform of the international tax system. It created a slim multilateral superstructure that left parallel [double taxation treaties] intact, updated thousands of [double taxation treaties] in substance and procedure, and managed to impose collective minimum standards while allowing states the flexibility to contract out of and around other parts of the [BEPS Convention].37Aschner, supra note 165, at 53.37

The BEPS Convention achieved such reform because of its flexible nature, which has led to 103 states to sign the Convention as of June 2024.38BEPS Multilateral Instrument, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/beps-multilateral-instrument.html.38 The success of the BEPS Convention is further underscored by its consideration in the UNCITRAL Working Group III discussions, where states are proposing it as a model for reforming the system due to its flexibility. In its submission of October 2019, the Government of Colombia stated:

Colombia considers that the [BEPS Convention] offers an enormous advantage as it has a large degree of flexibility, such that UNCITRAL member States can accommodate themselves to it according to their interests and concerns . . . the advantage of following the [BEPS Convention] is the flexibility it represents. Certainly, given the broad range of countries and jurisdictions that are involved in developing ISDS reform, the [BEPS Convention] would be flexible enough to accommodate the positions of different countries and jurisdictions while remaining consistent with the purpose of the reform, while establishing some “minimums” or “pillars” to be agreed by the States.39Secretariat of UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible reform of investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS): Submission from the Government of Colombia ¶¶ 5, 26, U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.III/WP.173 (Jun. 14, 2019), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v19/049/53/pdf/v1904953.pdf.39

Additionally, when viewed through the lens of the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency standard, this proposal seems valuable. As previously stated, the Kaldor-Hicks efficiency standard focuses on the net gain in societal welfare, even if it creates both winners and losers.40Pacces & Visscher, supra note 5, at [9].40 This standard acknowledges that a potential regulation “will nearly always create winners and losers . . . the hope is that those who lose from one policy will benefit from others and that on net, everyone will gain as aggregate wealth is increased.”41Miceli, supra note 15, at 7; see also Parisi, supra note 1, at 267 (“[T]he Kaldor-Hicks criterion requires a comparison of the gains of one group and the losses of the other group. As long as the gainers gain more than the losers lose, the move is deemed efficient.”).41

First, the primary beneficiaries of the proposed regulation would be the individuals for whom the system was created, namely investors and states. A flexible regulation of third-party funding would empower states to craft and implement provisions best aligned with their specific interests. For instance, provisions on frivolous claims,42UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Third-party funding, supra note 59, ¶ 34.42 disclosure rules,43Thrasher, supra note 146, at 2945-46; see also UNCITRAL Working Grp. III, Possible solution, supra note 73, ¶¶ 26-32; ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 60, at 81.43 or security for costs44Shao, supra note 109, at 447; see also ICCA-Queen Mary Task Force Report, supra note 63, at 145.44—well-known concerns in the ISDS system—are areas that states would likely seek to regulate.

In turn, investors would benefit from a clearer legal framework on third-party funding, as the purpose of the regulation is not to ban third-party funding but rather to “accommodate this tripartite relationship brought by the participation of third-party funders and to make their responsibilities commensurate with their entitlements.”45Shao, supra note 109, at 447.45 In fact, the worst-case scenario for investors who favor ISDS would be for states to opt out of the system, as Australia did in 2011,46Thrasher, supra note 146, at 2949.46 forcing investors to resolve disputes in national courts rather than through international arbitration.

Second, the potential losers from the regulation could include funders, brokers, and lawyers who currently benefit from the practice of third-party funding. Regulation would primarily impact funders. However, as surprising as it may seem, regulation could actually benefit—and, in Kaldor-Hicks terms, compensate—funders. In interviews conducted by Can Eken, funders were asked their opinions on regulation. While the majority believed regulation was unnecessary,47Can Eken, supra note 90, at 131.47 some funders expressed a preference for regulation, citing interests such as ensuring “every funder to operate at the same high level” or changing “the way the outside world perceives [third-party funding] practice.”48Id. at 131, 133.48

Based on the above, preserving ISDS should be seem as a way to generate greater aggregate welfare for both the winners and losers of the regulation. The risk of abuse within the third-party funding system is a real and pressing concern.49Thrasher, supra note 146, at 2944; Garcia, supra note 146, at 2919.49 Clear regulation of this matter could bolster the legitimacy of the ISDS system, which is currently under scrutiny,50Thrasher, supra note 146, at 2945, 2949.50 and preserve its original purpose of promoting and protecting foreign investment while enhancing the system’s long-term sustainability. Therefore, in Kaldor-Hick efficiency terms, the regulation could promote general societal welfare by improving the system for the primary stakeholders (states and investors) while compensating the regulation’s potential losers (funders) with the benefits they themselves have identified from a potential regulation, as highlighted above.

Conclusion

Third-party funding is a complex issue involving stakeholders outside the ISDS system. In some instances, this funding mechanism is employed primarily for economic purposes, potentially enabling the submission of frivolous ISDS claims. Moreover, such utilization poses a risk for states engaged in arbitration proceedings because it jeopardizes their ability to recover legal costs incurred in their defense.

Therefore, this article advocates for the implementation of an opt-in multilateral instrument to reform third-party funding in ISDS. This instrument could serve as a practical alternative to address the challenges associated with third-party funding by incorporating regulatory provisions within its text. To pre-empt potential debates among states regarding the provisions of this instrument, the analysis illustrates that adopting a flexible structure, akin to the BEPS Convention, would obviate the need for extensive deliberation. States would have the autonomy to select provisions aligning with their specific needs. The efficiency analysis conducted from an economic perspective, along with the application of the subsidiarity principle, supports this conclusion.

As articulated in the introduction, this article concludes that regulation of third-party funding is the singular solution to rectify the current drawbacks undermining the legitimacy of the ISDS system. It emphatically asserts that regulation is not merely a way but the only viable path forward.